Lab to life

When it comes to health innovations and progress, UCLA is a globally recognized leader with a novel superpower. Across the UCLA College — the academic heart of the university — experts in chemistry, psychology, urban sustainability and beyond are bringing their research to bear in tangible ways. Against the shifting social and political landscapes of the post-pandemic world, they are joining forces across campus and partnering with community, industry and government stakeholders. Their shared mission: to tackle some of the greatest human health challenges of our time — and to bolster public understanding of the power of science. These are just a few of their stories.

ENGINE OF CREATIVITY

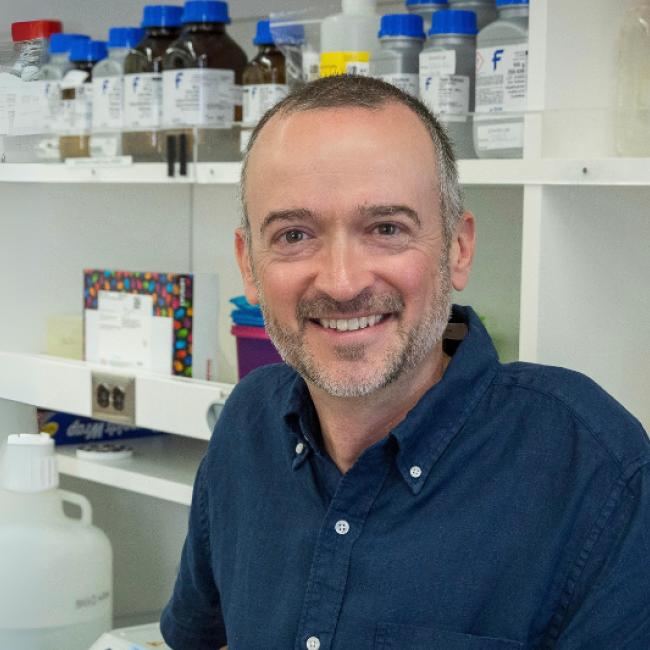

Catalyzing new treatments

Some of the farthest-reaching health innovations and discoveries are first sparked by personal experience.

As a college undergraduate in the 1990s, Stuart Conway took a course taught by biochemist Roger Newton, who led the team that developed salmeterol — a drug that, at the time, had been a breakthrough in asthma management.

“I have asthma, so that really was a key moment — this guy had invented a molecule that, when I put it in my body, I could feel the effect of what that did,” says Conway, who today serves as UCLA’s Michael and Alice Jung Endowed Professor of Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery. “I remember being in his lectures and going, ‘That’s what I want to do.’”

The UCLA Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry welcomed Conway in 2023 as the inaugural holder of the chair, which was endowed by distinguished professor Michael Jung and his wife, Alice. The couple’s gift followed the discovery by Jung and UCLA colleagues of the prostate cancer drugs Xtandi and Erleada, credited with saving thousands of lives. Conway’s lab encompasses drug discovery work in a range of areas, including cancers as well as diseases that don’t typically receive a large amount of attention or awareness.

“We’re interested in neglected tropical diseases — things like schistosomiasis and leishmaniasis, which affect hundreds of millions of people worldwide, but there’s not a big economic driver for developing drugs for them,” said Conway. “So I think academics have a key role to play in making drugs for those diseases as well.”

“To have a chance to enhance people’s lives makes all the obstacles the chemistry throws at us worthwhile.” —Ellen Sletten

Also critically in need of research are the muscular dystrophies, rare but lethal genetic disorders that cause progressive muscle weakness and wasting. Rachelle Crosbie, professor of integrative biology and physiology and of neurology, seeks ways to disrupt the course of these diseases and identify new targets for drug therapy. With a major philanthropic gift from the Dana and Albert R. Broccoli Charitable Foundation, her lab has been able to include a focus on the ultra-rare limb-girdle group of muscular dystrophies.

“One of the opportunities with rare disease is that the FDA considers accelerated approvals for any new treatments. So we can be creative and innovative, because the need is so dire to come up with novel therapies and see if those can make a difference,” Crosbie says. “And then, if that is the case, these innovations can be ported to other diseases that affect more people in the population, using those same techniques or approaches.”

Crosbie’s lab attracts many graduate and undergraduate researchers interested in making a difference — often, she says, because they have a family member who is affected. “I’ve also had undergraduates in the lab who themselves have a muscle-wasting disease,” she says. “So it can be very, very personal for everyone on the team.”

CHEMISTRY FOR A HEALTHY WORLD

Students, faculty, staff, alumni and friends gathered in April for the UCLA Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry’s inaugural “Chemistry for a Healthy World” event. Featuring presentations by Michael Jung, Heather Maynard, Ellen Sletten and Stuart Conway on their groundbreaking research, the event sparked conversations around recent advancements related to human health.

“The level of innovation and entrepreneurship that happens in the department of chemistry and biochemistry is truly amazing,” said Miguel García-Garibay, dean of physical sciences and senior dean of the UCLA College, at the event. “It’s unlike anything else that you’ll find in academic departments in other places.”

Transforming technologies

To achieve better patient outcomes, improving the tools and technologies that can save lives is paramount. A common danger for surgeons who operate to remove tumors is that cells too small to see with the human eye may remain embedded in the body’s tissue — meaning patients must later undergo additional surgeries to have them removed.

UCLA professor of chemistry Ellen Sletten and her collaborator Oliver Bruns of the National Center for Tumor Diseases Dresden in Germany have worked together for a decade on an innovative technology that addresses this challenge. In September, the two received the Helmholtz High Impact Award for developing a new medical imaging system that combines custom fluorescent dyes synthesized by Sletten and team with low energy short-wave infrared light that can pass through tissue and be detected with special cameras. These advancements will facilitate tumor detection and improve disease diagnosis.

“We hope our work will provide opportunities for low-cost diagnostic screening procedures, as well as enable diagnostics for conditions that currently have limited clinical tools, such as imaging lymphatic disease,” Sletten says. “To have a chance to enhance people’s lives makes all the obstacles the chemistry throws at us worthwhile.”

In the realm of medical devices, one of the most common — the catheter, a tube that is inserted into the body to add or remove fluids — can carry significant risk of infection. This is due to the body’s production of biofilm, a layer of microorganisms that forms and allows bacteria to multiply after the catheter is inserted. The risk can be particularly high for patients with chronic conditions who must use the devices long term.

“Something I never thought I’d experience as a chemist — two years ago, one of our first patients came back to UCLA to personally thank us for changing the quality of her life.” —Richard Kaner

Richard Kaner, a distinguished professor of chemistry and of materials science and engineering, is taking an innovative approach to this problem. A materials chemist who holds UCLA’s Dr. Myung Ki Hong Endowed Chair in Materials Innovation, Kaner and his team developed a hydrophilic coating that, when applied to a catheter, prevents the formation of biofilm altogether — meaning the bacteria never get a chance to multiply, and the risk of infection is eliminated. To bring this technology to the world, Kaner created the company SILQ Technologies Corp, which has produced positive outcomes for patients in clinical trials who have used the coated catheters.

“Something I never thought I’d experience as a chemist — two years ago, one of our first patients came back to UCLA to personally thank us for changing the quality of her life,” Kaner says, noting that the patient, who has muscular dystrophy, shared her story publicly to help spread the word about the new technology. “And all she asked is that we do for everybody in her situation what we’ve done for her. So we’re working on it. There are over 100 other medical products that need to be coated to prevent bacterial infections and fungal infections, and we can do that, and our success has been astounding. It’s the most exciting thing I’ve ever done.”

Kaner, Crosbie and Conway stress that such advancements are fueled by outstanding rising scientists in their labs — and collaborations across the UCLA College, the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and beyond.

“The engine that drives creativity is our community of trainees, including graduate students, postdoctoral fellows and undergraduates,” Crosbie says. “It’s a collaborative effort to make discoveries, and people really have to work together across disciplines. And folks that are new to research have an important role to play as well.”

DEMYSTIFYING REPRODUCTIVE SCIENCE

An urgent need

In 2021, UCLA stem cell biologist Amander Clark and Dean of Life Sciences Tracy Johnson discussed a shared vision to create a new academic hub on campus focused on reproductive science and health care. But when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade the following year, revealing gaps in public knowledge and in higher education programming, Clark says, the vision became urgent.

Today, Clark is concluding her second year as inaugural director of the UCLA Center for Reproductive Science, Health and Education, a cross-disciplinary home on campus for this vital work. Clark, an expert in reproductive science and professor in UCLA’s department of molecular, cell and developmental biology, and co-director Hannah Landecker have led a robust slate of activities aimed at changing the public conversation and advancing transformative research in the field. Speaking at an Oct. 3 event on campus, Clark revisited the mission at the heart of these efforts.

“As reproductive health and justice have become part of the national conversation, a pressing need has emerged to ensure that reproductive science research, education and outreach are keeping pace with the public need for accurate, fact-based information and continued scientific innovation that will improve the lives of people and their families,” she said.

“It is humbling to consider the role we play as scientists and educators to alleviate suffering and provide hope.” —Amander Clark

Taking a multi-pronged approach, CRSHE operates in partnership with the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, the UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, the Institute for Society and Genetics and the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. Key research areas include fertility and sexual health; infertility; and maternal health, pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes, and the center conducts activities ranging from public presentations to an art installation featuring the work of a UCLA alumna. CRSHE works with collaborative partners across campus, including the Center for the Study of Women.

The center’s distinguished speaker series is open to the public and has so far brought two field-leading experts to UCLA’s campus. In February, L.A. County Supervisor Holly J. Mitchell addressed the Black maternal health crisis and advocated for the role of doulas in improving health and birthing outcomes for Black women; in October, award-winning Caltech scientist Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz focused on infertility, which Clark has noted affects about 17% of the adult population worldwide. Through these presentations, and by offering fellowships, awards, career development activities, undergraduate courses and a monthly seminar series, CRSHE seeks to expose students to the reproductive workforce and build a pipeline for future careers.

“By supporting scientific discovery and public engagement, the center provides knowledge and understanding to improve the quality of life and address societal challenges for millions of people who suffer from reproductive disease or disorders of pregnancy,” says Clark. “It is humbling to consider the role we play as scientists and educators to alleviate suffering and provide hope.”

SPOTLIGHT ON REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE

With all eyes on the future of reproductive rights, the second annual UCLA Barbra Streisand Center lecture was held Oct. 16 on campus to provide deeper insights into the current crisis — and what’s next. Opening with remarks by Dean of Social Sciences Abel Valenzuela, the event featured a keynote address by legal scholar and reproductive justice expert Michele Bratcher Goodwin, who said the Supreme Court’s decisions have resulted in consequences leading far beyond attacks on abortion rights. “We have to begin to see the attacks on reproductive health care as attacks on our broader democracy,” Goodwin said.

Housed at the Center for the Study of Women, the UCLA Barbra Streisand Center was established in 2021 and made possible by the vision and generosity of Barbra Streisand. The Streisand Center will become the future Barbra Streisand Institute at UCLA, a forward-thinking institute dedicated to finding solutions to the most vital social issues.

DEMOCRATIZING MENTAL HEALTH SOLUTIONS

Sharing critical knowledge

Since the U.S. Surgeon General sounded the alarm on youth mental health in 2021, the crisis has only intensified given the ongoing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Bruce Chorpita, a UCLA professor of psychology and of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences with three decades of experience in children’s mental health, is taking a long view with a strategic approach aimed at improving young people’s lives.

“Oftentimes, people think the problem is that we don’t know the answers to the big questions about children’s mental health,” he says. “I would argue the problem is that we have an enormous amount of answers that are unknown to most people. And so my work is guided by the principle of democratizing science — finding out what we can build to better communicate those answers to the people who need them in order to effectively help children do better.”

“My work is guided by the principle of democratizing science — finding out what we can build to better communicate those answers to the people who need them in order to effectively help children do better.” —Bruce Chorpita

Chorpita’s lab, the Child FIRST Program at UCLA, works to better steward, map and deliver that vast universe of answers in collaboration with industry and community partners. He and his team perform clinical trials and traditional science, but also act as engineers — developing tools and appliances that serve as a kind of GPS, he says, in the hands of mental health care providers, counselors and even patients’ families. The results are far-reaching: Chorpita and his team have built and tested packages that are now used in 120 countries by tens of thousands of practitioners, and that benefit around 50,000 families per year served in Los Angeles public schools and the county mental health system.

As part of his efforts to scale mental health care treatments, Chorpita is also a co-founder and board officer for PracticeWise, a company that has educated and supervised providers around the world, including more than 4,000 in Los Angeles County. He credits UCLA with driving this progress by being open to and supportive of these collaborations outside campus.

“We’ve done great things, but they’re possible because we’re allowed to ask these big questions,” Chorpita says. “I’m humbled every day to be a part of this institution whose mission is really about improving lives.”

HEALTH HUMANITIES: A HOLISTIC APPROACH

Emerging at the intersection of health, medicine and the humanities, the rising field of health humanities — which incorporates everything from examining cultural and ethical dimensions to delving into storytelling and critical reflection — promotes empathy and a deeper comprehension of patient experiences.

Under the leadership of Dean Alexandra Minna Stern and Whitney Arnold, assistant professor of comparative literature and chair of the health humanities theme in the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, and building on growing interest from students, the UCLA Division of Humanities is creating a health humanities minor slated to launch by the end of 2025.

“Every division and discipline recognizes how important the health humanities are, and it’s so exciting that we have this opportunity to lead and shape the direction of this field,” says Arnold. “The impact of this work across the university — and the world — is deeply inspiring.”

Empowering Gen Z

Community engagement drives the work of the UCLA Center for the Developing Adolescent, which advances understanding of the science of adolescent development to improve policies and programs that support young people’s well-being. Led by co-executive directors Andrew Fuligni, professor of psychology and psychiatry, and Adriana Galván, dean of undergraduate education and professor of psychology, the CDA promotes a nuanced and empowering perspective on adolescence — roughly ages 10 to 25 — as a critical window of opportunity for positive growth and development.

By sharing this knowledge with policymakers, schools, practitioners and the general public, the CDA provides a vital resource for improving youth outcomes. Galván provided testimony to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court about adolescent brain development, specifically around sensation-seeking and risk-taking behaviors, which informed their decision earlier this year to abolish life sentences without parole for young people aged 18 to 20. Also this year, the Administration for Children and Families within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services shared CDA’s work in policy guidance encouraging the state, local, territorial and tribal agencies that administer their programs to incorporate strategies to meet the unique developmental needs of adolescents. Specifically, ACF highlighted CDA’s summary of the key developmental needs of adolescents and its two youth engagement guides.

The CDA also hosts the Youth Scientific Council on Adolescence, bringing together high school and undergraduate students to share perspectives, learn about the science of adolescence and help communicate it to larger audiences — ensuring young people are directly informing the work.

“One of our big findings is that adolescents want to see more platonic relationships, which is so developmentally normal. Instead of these fake, sex-love triangles, teens want to see: How do I make a friend?” —Yalda Uhls

Engaging teens and young adults themselves in the process of addressing youth mental health is central to the mission of the Center for Scholars & Storytellers at UCLA, which is now concluding its sixth year of connecting Hollywood content creators with developmental science research. The center’s annual Teens and Screens study, which has been covered by national media outlets and shared widely within the entertainment industry, reveals what young people want to see — and how they want to see themselves portrayed — on the screens they look at every day.

“One of our big findings is that adolescents want to see more platonic relationships, which is so developmentally normal. Instead of these fake, sex-love triangles, teens want to see: How do I make a friend? And what are the conflicts? Just real-life, relatable stuff,” says Yalda Uhls, the center’s founder and CEO. A former senior film executive, Uhls earned both her M.B.A. and her Ph.D. in developmental psychology at UCLA before becoming an assistant adjunct professor. “And I really believe that in a few years, because we keep getting this finding and we’re getting it out there, that you’re going to see more content like that targeted to adolescents.”

At its annual Teens and Screens summit on UCLA’s campus, the center puts youth activists in front of storytellers along with scientists, researchers and public health leaders to engage in crucial conversations about mental health and inclusive representation on screen. It’s all, Uhls says, part of the center’s efforts to foster a community invested in making a positive impact on young people’s lives.

NOURISHING PEOPLE AND PLANET

Feeding the future

Research shows that climate change not only impacts existing human health conditions, it creates new ones — particularly through its effects on our food, water and the air we breathe. UCLA scientists are targeting ways to both feed and protect the planet by developing more sustainable food systems.

For Steve Jacobsen, distinguished professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology and of biological chemistry, the motivation is personal. Growing up on a family farm in California, he says, allowed him to witness the positive impacts of agricultural improvements and sparked his interest in moving beyond basic research to work with applied aspects. Jacobsen’s lab focuses on how gene expression is regulated in plants and develops tools for the modification of plant genes using the CRISPR genome-editing technique.

“The improvement of crop plants is much needed as resources required to grow crops become limited, and as climate change alters growing conditions. The tools we are developing could be part of the solution,” Jacobsen says. “Genome editing provides a method for producing crop plants with higher yields as well as resilience to higher temperatures and higher disease pressures.”

“Given the pressures on our land, resources and water, and with pandemics and natural disasters impacting our food systems, there’s a real need for complementary methods of protein production that can help to meet the world’s growing demand.” —Amy Rowat

Meat, an essential human food staple, continues to be a vital source of protein for people around the world. But today’s conventional livestock agriculture creates harmful impacts on the environment and human health — from methane emissions to the use of antibiotics in farmed animals, which can cause antibiotic resistance in humans.

Emerging science and technology, however, are poised to offer more sustainable strategies. Amy Rowat, UCLA’s Marcie H. Rothman Presidential Chair in Food Studies and inaugural faculty director of the Rothman Family Institute for Food Studies at UCLA, has made headlines for her research into cultured meat, which is grown from cells instead of taken from slaughtered animals.

“The concept itself is not new — Winston Churchill described the concept of growing meat from animal cells ex vivo back in 1931. The first cultivated beef burger was demonstrated in 2013 by a professor in the Netherlands, but it was very expensive and not tractable as a dietary source of nutritious animal proteins,” says Rowat, a professor of integrative biology and physiology in the UCLA College and a member of the bioengineering department in the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. “But given the pressures on our land, resources and water, and with pandemics and natural disasters impacting our food systems, there’s a real need for complementary methods of protein production that can help to meet the world’s growing demand.”

This fall, Rowat spearheaded the interdisciplinary Future of Food Fellows program at UCLA to foster the development of early-career scientists committed to building sustainable food systems. Launched with five inaugural graduate student fellows, including UCLA College doctoral student in chemistry Erika López-Lara, the program seeks to create a community of engaged scholars to move the field into the future.

ADDRESSING HEALTH DISPARITIES AFTER COVID

Distinguished psychology professor Vickie Mays received the 2024 Association for Psychological Science James S. Jackson Lifetime Achievement Award for Transformative Scholarship. Mays, whose research examines race-based discrimination and its impact on mental and physical health, worked with Congress after COVID-19 to address the disproportionate effects of the pandemic on the Black community.

The recipient of numerous awards for her research, academic leadership and service, Mays is also a professor of health policy and management at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, director of the UCLA BRITE Center for Science, Research and Policy and special advisor to the chancellor on Black life.

Protecting communities

Amid the growing impacts of climate change, some populations are much more severely affected than others. Stephanie Pincetl, professor at the UCLA Institute of the Environment and Sustainability and founding director of the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA, is a leading expert in urban sustainability with a focus on social and environmental justice. Work by Pincetl and her team has informed public policy in Los Angeles and California amid increasing wildfires and dangerously rising temperatures.

The center’s UCLA Energy Atlas project studied how the built environment in our cities impacts use of natural resources and affects health and well-being, particularly in underresourced communities. With increasingly high heat, Pincetl says, the use of air conditioning also increases — but besides disproportionately impacting people economically, this solution is unsustainable. Instead, she asserts, we need to address the thermal performance of our buildings to ensure they can better resist heat, eliminating the need to rely on air conditioning in the first place.

“We can always play a role — but we have to have the intention to play a role. It’s about living a life that includes being part of the public sphere and recognizing that we have a responsibility for our actions and for each other going forward.” —Stephanie Pincetl

“Short of growing our electricity consumption, which people will not be able to afford, we need to invest in the built environment far more,” Pincetl says. “It’s expensive in the short term, no question about it. But as a far longer-lasting approach to the situation, it will lead to more resilience and better health.”

As part of a decade of work on water self-reliance in Los Angeles, Pincetl this spring also co-authored a study pointing to ways that cities in the arid southwest can become less dependent on imported water.

“We have to rethink water, not as a commodity, but as a life-supporting, common resource that provides a common good,” she says. “If we reduce our irrigation, put in shade structures, think about the orientation of buildings, use groundwater conjunctively — that is, everybody uses it, and we recycle as much of the potable water as we possibly can — we’re making big strides towards becoming net zero urban water.”

Despite the vast challenges, Pincetl is committed to developing strategies to address the most harmful impacts, as well as engaging the public in envisioning a way forward.

“Helping people see these pathways is really important,” she says. “Too often we don’t allow ourselves to imagine what is possible, and we need to do that more.”

Among the most vulnerable populations is one also frequently overlooked: the more than 1 million people incarcerated in U.S. prisons, many of whom are already at higher risk of health impacts, and are disproportionately people of color and LGBTQ.

“Involving and training justice-system-impacted people guarantees the project will have a positive effect even before anything gets published, as we are ensuring our processes are building trustworthiness of science.” —Nicholas Shapiro

Medical anthropologist Nicholas Shapiro, assistant professor in the Institute for Society and Genetics at UCLA and a member of the IoES, this spring co-authored a study that revealed drinking water in many U.S. prisons likely contains the toxic “forever chemicals” known as PFAS — putting imprisoned people in danger of suffering a range of long-term health issues as a result. The study received national attention and was cited in the recently created Environmental Health in Prisons Act, with the senator leading the bill soliciting the UCLA research team’s help in drafting its scope.

Shapiro, who leads the Carceral Ecologies group of UCLA researchers focused on environmental injustices in the U.S. prison system, emphasizes that this work is most successful when those affected can play a role in designing and implementing the research.

“Involving and training justice-system-impacted people guarantees the project will have a positive effect even before anything gets published, as we are ensuring our processes are building trustworthiness of science,” he says. “In that way, our process is part of our product.”

Members of the greater community, Shapiro says, can also play a role in addressing environmental health disparities, whether by practicing solidarity with underprivileged neighbors through mutual aid work or voting for candidates who support science and advance equity-enhancing policies.

Pincetl, for her part, stresses the need for a shared sense of purpose when it comes to conserving resources in the interest of protecting the health of people and the planet. There is, she says, simply no other choice.

“We can always play a role — but we have to have the intention to play a role,” Pincetl says. “It’s about living a life that includes being part of the public sphere and recognizing that we have a responsibility for our actions and for each other going forward.”