UCLA researchers unite to develop immunotherapy they hope will transform ovarian cancer treatment

Key Takeaways

- An interdisciplinary team of UCLA scientists is working to create a therapy designed to both eliminate cancer cells and dismantle the tumor’s protective defenses, reducing the likelihood of recurrence.

- NKT cells are by nature compatible with any patient’s immune system, which eliminates the need to manufacture this therapy on a patient-by-patient basis.

- This potential "off-the-shelf" treatment is intended to be mass-produced from donated blood stem cells at a fraction of traditional immunotherapy costs.

For decades, the story of ovarian cancer treatment has often followed the same pattern: surgery, chemotherapy, recurrence, repeat.

This was the grim reality Dr. Sanaz Memarzadeh encountered as a second-year UCLA resident watching young women cycle through treatments only to face the disease’s inevitable return.

“Some of these women were relatively young and had already undergone multiple surgeries, but their cancer had come back, and they were dying,” she recalled. “I remember thinking, ‘There has to be something more we can do for these patients.’”

Her search for answers — through medical textbooks, research conferences and conversations with experts — revealed a sobering fact: treatment for ovarian cancer hadn’t meaningfully changed in 40 years. Even as advances in medicine brought breakthroughs for other cancers, ovarian cancer patients continued to face one of the highest recurrence rates (80%, according to the National Institutes of Health) and mortality rates of any malignancy.

“That’s when I really became motivated to focus my career on helping women diagnosed with gynecologic cancers,” she said. “And I made a vow to do that not just through standard clinical work but also through research.”

Determined to find a new path forward, Memarzadeh pursued a doctorate in molecular biology, training under Dr. Owen Witte, a leading cancer researcher and founder of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA.

In the Witte lab, she learned how to use stem cell-based models to study cancer at a fundamental level — how it originates, evolves and, most crucially, how it evades treatment.

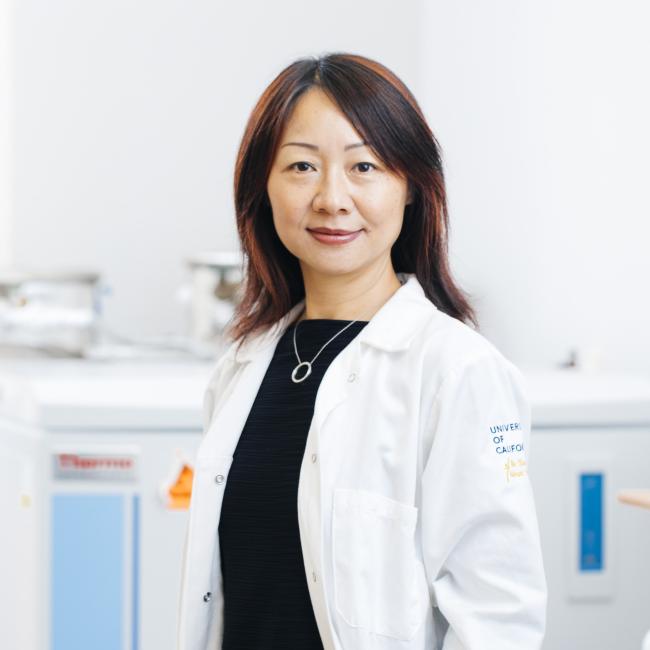

Now, as both a gynecologic cancer surgeon and a scientist, she divides her time between the operating room and her own laboratory at the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center. Her work is driven by a singular mission: to develop a therapy that will not only treat ovarian cancer but prevent its return.

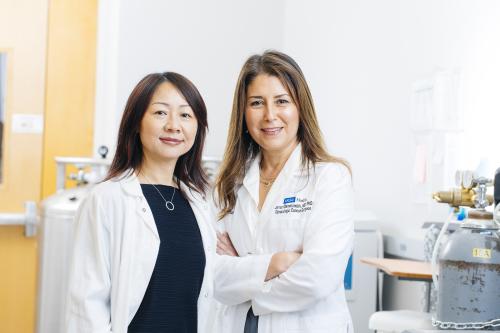

That mission led her to Dr. Lili Yang, an immunologist and fellow stem cell center member who has spent the past decade engineering a novel and more powerful type of cancer-fighting immune cell known as a CAR-NKT cell. Together, they are adapting this approach for ovarian cancer, working to create a therapy designed to both eliminate cancer cells and dismantle the tumor’s protective defenses, reducing the likelihood of recurrence.

What makes this therapy particularly promising is its “off-the-shelf” potential. Unlike traditional CAR-T cell treatments, which must be custom-made for each patient, CAR-NKT cells could be mass-produced from donated blood stem cells and used for any patient.

If successful, their work could transform ovarian cancer treatment, offering new hope for a disease that has long resisted medical advances.

Why does ovarian cancer keep coming back — and can it be stopped?

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynecologic malignancy, in large part because it is rarely detected early. With no routine screening tests and symptoms that often mirror common ailments, most cases aren’t diagnosed until the cancer has spread beyond the ovaries.

By then, the standard approach remains consistent: surgery followed by chemotherapy. Initially, this often works — the cancer shrinks and sometimes disappears. But in more than 80% of patients, it returns. And when it does, it’s different.

Each recurrence makes the disease more resistant to treatment, more aggressive and harder to eliminate. At a certain point, patients simply run out of options.

“The hardest conversations I have are with patients who’ve done everything — aggressive surgeries, round after round of chemo — only to have their cancer return,” said Memarzadeh, now a professor of obstetrics and gynecology, and molecular and medical pharmacology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

What makes ovarian cancer particularly lethal isn’t just its ability to spread undetected. It creates what scientists call an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment — essentially, a biological shield that prevents immune cells from attacking it. While other solid tumors like prostate, lung and breast cancer also create these microenvironments, ovarian cancer excels at this defense.

“Imagine the tumor as a fortress,” Memarzadeh, a member of the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, suggested. “It’s not just the cancer cells we’re fighting, but an entire ecosystem they’ve built around themselves.”

This hostile environment explains why CAR-T cell therapy, so effective against blood cancers, has fallen short against ovarian cancer and other solid tumors. The immune cells simply can’t breach these defenses.

This is where Yang’s novel, more powerful immune cell therapy offers new possibilities.

How CAR-NKT cells could overcome ovarian cancer’s defenses

An immunologist who has spent years studying the body’s natural cancer-fighting abilities, Yang has developed an approach that targets both the tumor and its defense system.

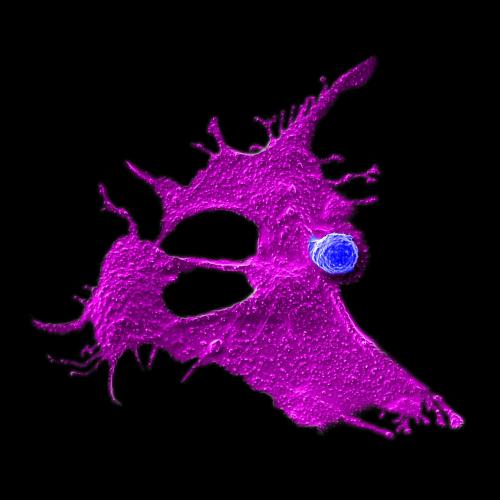

The key lies in a rare but powerful type of immune cell called invariant natural killer T cells, or NKT cells. Yang’s team has engineered these cells with a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, essentially giving them precision targeting capabilities while maintaining their natural ability to disrupt the tumor’s protective environment.

“What makes these CAR-NKT cells special is their dual action,” Yang, a professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics, explained. “They can directly kill cancer cells, but they also eliminate the immunosuppressive cells that protect the tumor. It’s like taking down both the fortress and its defenders at the same time.”

Another major advantage of CAR-NKT cell therapy is its potential for accessibility. Traditional cellular immunotherapies require collecting a patient’s immune cells, engineering them in a laboratory and returning them to the patient — a process that can take weeks and cost hundreds of thousands of dollars. Even for patients who can afford these therapies, the waiting period can allow aggressive cancers to advance.

Yang’s CAR-NKT cell therapy represents an entirely different paradigm.

NKT cells are by nature compatible with any patient’s immune system, which eliminates the need to manufacture this therapy on a patient-by-patient basis. Yang’s team has developed a method to mass-produce these cells from donated blood stem cells. A single donation could yield enough cells for thousands of treatments, potentially reducing costs from hundreds of thousands to approximately $5,000 per dose.

“Our goal is to eventually have frozen CAR-NKT cells ready at hospitals worldwide so any patient can access this therapy when needed,” said Yang, who is also a member of the cancer center. “Instead of waiting weeks for a custom treatment, doctors could prescribe these cells immediately, like any other medication.”

How collaboration is accelerating ovarian cancer research

The collaboration between Yang and Memarzadeh exemplifies the transformative potential of interdisciplinary research at the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center. Their connection runs deeper than shared laboratory space — it traces back to a shared scientific lineage through some of immunology’s pioneering figures. Yang trained under Nobel Laureate Dr. David Baltimore, while Memarzadeh studied under Witte, who himself had trained with Baltimore, creating an intellectual framework that helped bridge their different specialties.

The strength of their collaboration lies in how their different perspectives complement each other. Yang brings sophisticated immunology techniques and the breakthrough CAR-NKT cell technology, while Memarzadeh contributes crucial insights from the front lines of cancer treatment along with patient-derived tumor samples and clinical data.

“These interdisciplinary collaborations, bringing different expertise together to solve challenging problems, are critical,” Memarzadeh emphasized. “Obviously, this is a challenging problem — otherwise, it would have been solved by now.”

Laboratory studies using patient-derived tumor samples have shown that CAR-NKT cells can eliminate even highly resistant ovarian cancer cells while transforming the tumor environment to inhibit new cancer growth.

“What’s particularly exciting is how these cells persist and maintain their protective effects long after initial treatment,” Memarzadeh noted. “We’re not just seeing tumors shrink — we’re seeing changes that could make it much harder for the cancer to return.”

With support from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the team is now working to complete the preclinical studies necessary to apply to the Food and Drug Administration to open a clinical trial.

For this work, they’ve partnered with fellow UCLA faculty members — bioinformatician Dr. Matteo Pellegrini and biostatistician Dr. Jin Zhou — whose expertise in data analysis and statistical modeling is critical for translating their findings into a rigorous, clinically viable therapy.

Could CAR-NKT cell therapy work for other types of cancer?

While their initial focus remains on ovarian cancer, the implications of this work stretch far beyond. The same mechanisms that make ovarian cancer so resistant to treatment are shared by many other solid tumors — from lung cancer to breast cancer and beyond.

“We’re already seeing promising results in preclinical studies in other cancer types,” Yang said. “The ability to break down a tumor’s defenses while attacking the cancer cells could be a game-changing approach for many difficult-to-treat cancers.”

The lab is also working on next-generation improvements to the therapy, including ways to make the CAR-NKT cells even more potent and developing methods to produce them from induced pluripotent stem cells.

For Memarzadeh, this work represents the fulfillment of that early promise she made in the cancer ward.

“Every time I have to tell a patient their cancer has returned, I think about how close we are to changing that conversation,” she said. “We’re not just developing another treatment — we’re working to fundamentally change the course of this disease.”

Explore more stories of impact in our special 20th anniversary report — celebrating two decades of transformative stem cell research.