UCLA plays pivotal role in first gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Scientists at the Center for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy at UCLA have been making strides toward better treatments for the disease the organization is named for, recently helping get Food and Drug Administration approval for Sarepta’s gene therapy Elevidys.

UCLA was one of the first sites to conduct clinical trials of the drug — which Time magazine called one of the best inventions of 2024 — and has treated 12 patients commercially since the drug’s expanded FDA approval in June. An additional 34 patients are currently seeking insurance approval.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, or DMD, is a progressive muscle-wasting disease that begins in childhood and leads to premature death as the muscles that power the heart, lungs and other vital organs fail. DMD affects many systems of the body, requiring care from multiple specialists, including neurologists, cardiologists, pulmonologists, gastroenterologists, nephrologists, endocrinologists and orthopedists. UCLA’s Center for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (CDMD) was founded to provide multidisciplinary care, conduct translational research and improve access to clinical trials and treatments.

Feb. 28, 2025, is Rare Disease Day. Find out more about the annual global observance here.

The CDMD multidisciplinary care model brings all specialists together under one coordinated care system. This model has added 10 years to the average life span of patients with Duchenne, with some now living into their 30s.

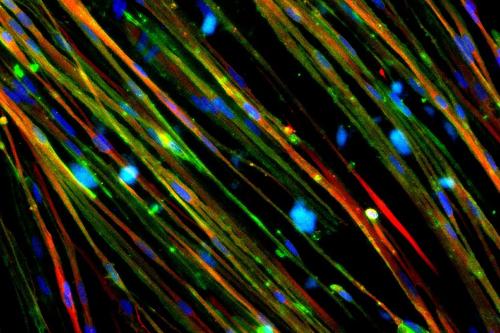

Duchenne is caused by a mutation in the gene for the dystrophin protein, which protects muscle cells from damage and loss. CDMD researchers are currently discovering ways to increase the efficacy of Elevidys gene therapy and are leaders in describing the effects at single-cell resolution.

“Our biopsies of pre- and post-gene therapy samples have been the first to see long-term microdystrophin expression beyond one year, and we are the first to see sustained expression of dystrophin seven years out, and in patients over 25 years of age,” said Dr. Stanley Nelson, a professor of human genetics, pathology and laboratory medicine, pediatrics, neurology and psychiatry and co-director of the CDMD (microdystrophins are shorter forms of the protein that are about one-third the size of the full dystrophin protein).

The Center for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy recognized over a decade ago that gene therapy treatments were coming and began fundraising to support the early clinical trials of Elevidys GT, helping pave the way for FDA approval. UCLA has also been one of the few institutions studying nonambulatory patients with Elevidys GT.

“Elevidys GT is not a cure and cannot reverse muscle damage already done. There are clearly limitations to its efficacy, and the CDMD researchers are working to discover druggable targets that promise to increase efficacy if drugs targeting them are combined with GT,” said Carrie Miceli, a professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics and co-director of the CDMD.