Study connects genetic risk for autism to changes observed in the brain

Key Takeaways

- The study by UCLA scientists is the first to identify a potential mechanism that connects changes occurring in the brain in autism spectrum disorder directly to underlying genetic causes.

- Identifying these types of complex molecular mechanisms could eventually help lead to the development of therapeutics to treat autism.

- The research is part of a larger National Institutes of Health initiative that seeks to uncover the mechanisms behind neurodevelopmental conditions like autism and mental illnesses like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

A new study led by UCLA researchers has unveiled the most detailed view of the complex biological mechanisms underlying autism, showing the first link between genetic risk for the disorder and observed cellular and genetic activity across different layers of the brain.

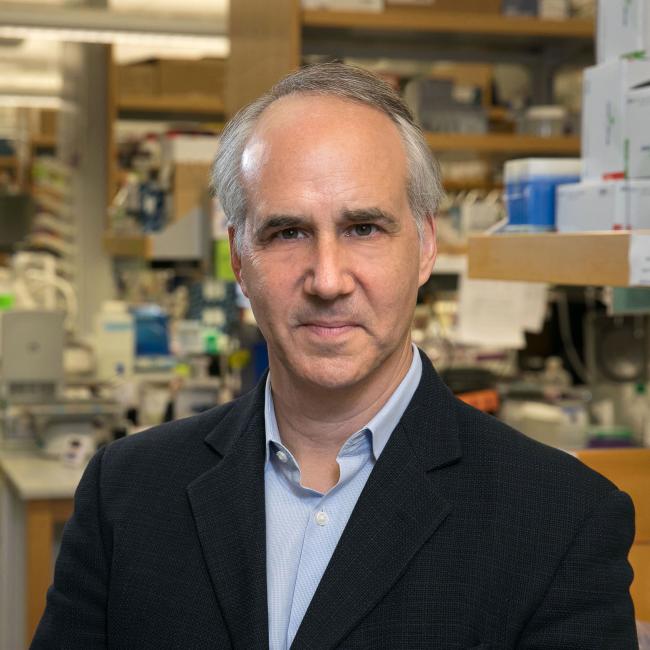

Their study is part of a second package of studies from the National Institutes of Health consortium PsychENCODE. Launched in 2015, the initiative, chaired by UCLA neurogeneticist Dr. Daniel Geschwind, is working to create maps of gene regulation across different regions of the brain and different stages of brain development. The consortium aims to bridge the gap between studies on the genetic risk for various psychiatric disorders and the potential causal mechanisms at the molecular level.

“This collection of manuscripts from PsychENCODE, both individually and as a package, provides an unprecedented resource for understanding the relationship of disease risk to genetic mechanisms in the brain,” Geschwind said.

Geschwind’s study on autism, one of nine published in the May 24 issue of the journal Science, builds on decades of his group’s research profiling the genes that increase susceptibility to autism spectrum disorder and defining the convergent molecular changes observed in the brains of individuals with autism. However, what drives these molecular changes and how they relate to genetic susceptibility in this complex condition at the cellular and circuit level are not well understood.

Gene profiling for autism spectrum disorder, with a few exceptions in smaller studies, has long been limited to using bulk tissue from brains of autistic individuals after death. These tissue studies are unable to provide detailed information such as the differences in brain layer, circuit level and cell type–specific pathways associated with autism or the mechanisms for gene regulation.

To address this, Geschwind used advances in single-cell assays, a technique that makes it possible to extract and identify the genetic information in the nuclei of individual cells. This technique provides researchers the ability to navigate the brain’s complex network of different cell types.

More than 800,000 nuclei were isolated from post-mortem brain tissue of 66 individuals ranging in age from 2 to 60, including 33 individuals with autism spectrum disorder and 30 neurotypical individuals who acted as controls. The individuals with autism included five with a defined genetic form called 15q duplication syndrome. Each sample was matched by age, sex and cause of death, balanced across cases and controls.

Through this, Geschwind and his team were able to identify the major cortical cell types affected in autism spectrum disorder, which included both neurons and their support cells, known as glial cells. In particular, the study found the most profound changes in the neurons that connect the two brain hemispheres and provide long range connectivity between different brain regions and a group of interneurons called somatostatin interneurons, which are important for the maturation and refinement of brain circuits.

A critical aspect of the study was the identification of specific transcription factor networks — the web of interactions whereby proteins control when a gene is expressed or inhibited — that drive the changes that were observed. Remarkably, these drivers were enriched in known high-confidence autism spectrum disorder risk genes and influenced large changes in differential expression across specific cell subtypes. This is the first time that a potential mechanism connects changes occurring in brain in ASD directly to the underlying genetic causes.

Identifying these complex molecular mechanisms underlying autism and other psychiatric disorders studied could work to develop new therapeutics to treat these disorders.

“These findings provide a robust and refined framework for understanding the molecular changes that occur in brains in people with ASD — which cell types they occur in and how they relate to brain circuits,” Geschwind said. “They suggest that the changes observed are downstream of known genetic causes of autism, providing insight into potential causal mechanisms of the disease.”

The PsychENCODE papers are presented as a collection on the Science website.

Notes

The studies received grant funding from the National Institutes of Health.