Standard method for deriving stem cells may be better for use in regenerative medicine

Scientists at the UCLA Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research have discovered an important naturally occurring process in the developing human embryo that can be lost when embryonic stem cells are derived in the lab.

The discovery provides scientists with critical information regarding the best method for creating stem cells for regenerative medicine purposes, such as cell transplantation or organ regeneration. The discovery also provides insight into how information that is passed from an unfertilized egg to an embryo may impact the quality of the embryo and subsequently, the birth of healthy children.

The findings were published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

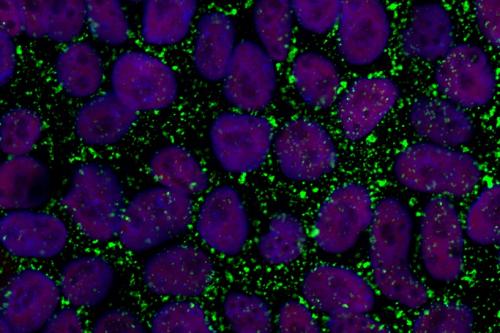

The research focuses on DNA methylation — a biochemical process that occurs naturally in DNA — in the early embryo and in stem cells created from embryos.

DNA methylation plays a role in how genetic information is used in the body. Correct DNA methylation of particular genes is critical for normal human development, and it remains critical in maintaining healthy cells throughout a person’s lifespan. It also helps maintain an embryonic stem cell’s ability to develop into any cell in the body.

The researchers made two important discoveries about DNA methylation. First, they discovered that an early-stage embryo, or blastocyst, retains the DNA methylation pattern from the egg for at least six days after fertilization. Prior to this discovery, scientists thought that methylation memory from the egg was only retained for a few hours after fertilization.

“We know that the six days after fertilization is a very critical time in human development, with many changes happening within that period,” said Amander Clark, the study’s lead author and a professor and vice chair of molecular, cell and developmental biology in the life sciences at UCLA. “It’s not clear yet why the blastocyst retains methylation during this time period or what purpose it serves, but this finding opens up new areas of investigation into how methylation patterns built in the egg affect embryo quality and the birth of healthy children.”

The team’s second discovery reveals that using a recently adopted method to derive stem cells from embryos in a petri dish results in loss of methylation.

In the early embryo, the blastocyst stage of development lasts for less than five days. The less mature human embryonic cells that exist at the beginning of blastocyst development are called “naïve” embryonic cells. It is thought that at the time of implantation, these naïve embryonic cells reach a more mature state. They are then called “primed” embryonic cells, because they are primed to become every cell type in the body.

In 1998, when the first human embryonic stem cells were derived, scientists used a method that created primed stem cells. This was the standard method until recently, when scientists started using a different method that preserves the naïve stem cell state.

“In the past three years, naïve stem cells have been touted as potentially superior to primed cells,” Clark said. “But our data show that the naïve method for creating stem cells results in cells that have problems, including the loss of methylation from important places in DNA. Therefore, until we have a way to create more stable naïve embryonic stem cells, the embryonic stem cells created for the purposes of regenerative medicine should be in a primed state in order to create the highest-quality cells for differentiation.”

The two other UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center faculty members who collaborated on the study are Kathrin Plath, professor of biological chemistry in UCLA Life Sciences; and Steven Jacobsen, professor of molecular, cell and developmental biology in UCLA Life Sciences and an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

To further this research, Clark and Plath plan to work together to determine the optimal conditions for creating naïve embryonic stem cells that are more stable and retain methylation at places in the genome where it is most needed.

All human embryonic stem cells derived at the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center are obtained from stored frozen embryos donated with informed consent by individuals or couples who have completed in vitro fertilization.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center.