Amyloid assassin: Lecanemab makes strides in fight against Alzheimer’s

Alzheimer's disease is a condition that not only challenges those who suffer from it, but also the scientists and doctors who strive to combat it. But a new treatment has emerged that offers a glimmer of hope by slowing progression of the disease.

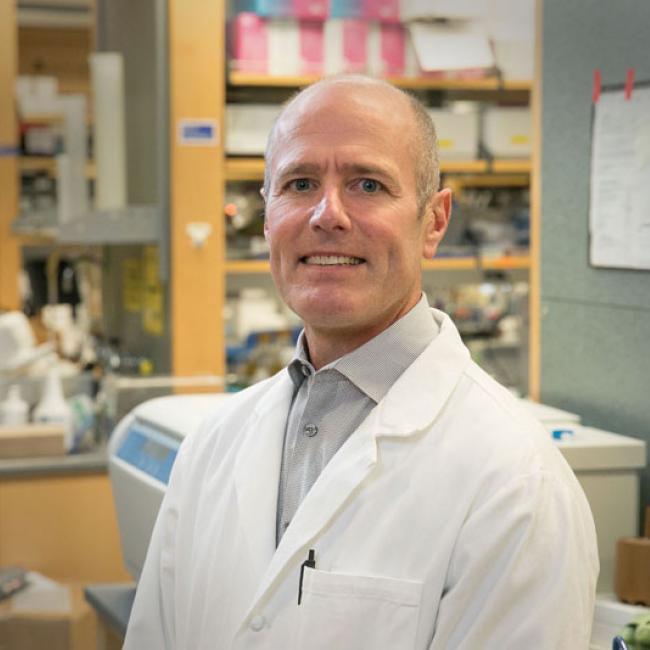

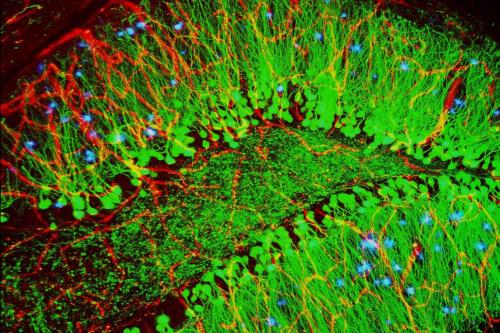

Lecanemab is an infusion that targets amyloid, one of the two abnormal proteins that accumulate in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease, explained S. Thomas Carmichael Jr., MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Neurology at UCLA Health. “Lecanemab recognizes amyloid. Once it’s infused into the bloodstream, it crosses into the brain, where it binds to this abnormal protein and causes the brain to clear it into the bloodstream and then get rid of it.”

While it decelerates progression of the disease, the drug does not reverse Alzheimer's.

The Easton Center for Alzheimer's Research and Care at UCLA was instrumental in the multicenter Clarity AD trial, which is now in phase 4 clinical trials after the FDA approved the efficacy and safety of lecanemab in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. The findings were promising: Not only did lecanemab diminish the presence of amyloid indicators, it also slowed the rate of cognitive and functional deterioration when compared with the control group receiving a placebo.

“At the clinical trial level, people essentially had a six-month delay in disease progression, compared to those who didn't receive lecanemab,” Dr. Carcmichael said. “Lecanemab remarkably clears one of the bad proteins, but there's kind of a mismatch – while there is this profound effect of it clearing up one of the bad proteins, there’s only a modest effect on cognitive function.”

This mismatch is at the heart of a broader debate within the scientific community: While amyloid clearance is achieved, the cognitive benefits are not as dramatic as researchers hoped. “This is where the controversy is,” Dr. Carmichael said. “For many years, scientists thought that amyloid was the main cause of mental decay in patients with Alzheimer's disease. What this tells us, however, is that we can remove amyloid, and that helps, but surprisingly little.”

The hope for the future of lecanemab as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease is that it will pave the way for further advances and newer therapies that will lead to more significant long-term outcomes.

Rather than being a standalone therapy, Dr. Carmichael foresees lecanemab as part of a multi-pronged approach to treating Alzheimer’s disease. “This will be one of our tools to treat Alzheimer's disease, but we'll need others,” he said. “I'm not sure what those will be. But clearly, there's going to be several drugs that we will need” for a comprehensive treatment strategy.

While the FDA approved lecanemab, it put another, similar Alzheimer’s drug, donamemab, on hold for further safety review. That decision has surprised many in the scientific community, including Dr. Carmichael. Both drugs are monoclonal antibodies that target amyloid, and both carry risks of brain swelling and bleeding. “The two drugs are very similar in their systems of care and delivery, so I'm not sure why they would be so cautious about approving donanemab after approving Lecanemab,” Dr. Carmichael said. “It may be because of a third drug, which was the first one and was highly controversial, called aducanemab. The FDA flagged that drug, and perhaps that has made them move cautiously going forward.”