What’s the difference?

The core question that concerns Dr. Stephanie Correa is how the brain regulates temperature and energy balance differently in males and females. “We want to know how estrogens” — the primary hormone produced by the ovaries — “act on the hypothalamus to alter temperature homeostasis and metabolic health,” she says. “Why would something so crucial to biological function be sensitive to sex and sex hormones?” By using mouse models to answer that question, she hopes to enhance understanding of the underlying causes of weight gain and hot flashes in postmenopausal women and provide future scientists with broader knowledge to develop treatments.

When did you first start to think about science?

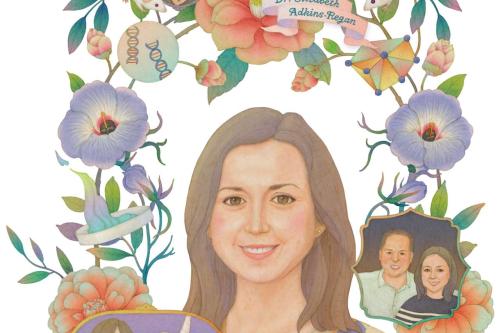

I always liked science, but I never knew that I could do science until I was in college. When I was a kid, “science” was Bill Nye in a bow tie on TV. Nobody I saw who was a scientist looked like me — not female and not Latina. I didn’t know that scientific research could be a career for me. But in college, I got to work with professors and talk with professors about science, and many of them were women, and I realized that science was something I could do.

What was your first experiment?

There was a science fair in the sixth grade and in my science class we had to come up with experiments. The teacher gave us some options, and I picked one, but I thought it was rather limited — it involved putting black and white fabric over ice in a cup to see how the different colors might reflect or absorb heat. I expanded on that and used other colors of fabric, and I also controlled for the fabric thickness, and I made predictions about how the different colors and fabrics would absorb or reflect heat. I won second place.

What has been the greatest challenge in your work?

The greatest challenge has been trying to frame what I work on as important to the overall field of biological sciences. Historically, working on female subjects has been treated as a side project, or an epiphenomenon, and not central to the problems being explored. My challenge has been to promote recognition that research involving female subjects is as essential to understanding these issues as is research involving male subjects. If you understand how a biological process works only in males, then you don’t really understand how it works.

Where does your inspiration come from?

It really comes from the biology — the animals that we study or the subjects we are investigating or the data we are collecting. Taking all that information and trying to figure out what the animals are trying to tell us — what is the truth — is the most exciting and inspiring thing.

Who is your science hero?

My science hero is Art Arnold (Distinguished Professor of Integrative Biology & Physiology), here at UCLA. I met him as a fourth-year PhD student at Cornell, and we got to talking about sexual differentiation and sex differences, and we just had a really exciting conversation. In my eyes, he was someone who was famous, and it was so inspiring that he would engage with me about science. Now, I am his colleague at UCLA, and he still is the hero who continues to inspire my work.

Where are you happiest?

In my lab. When I was a post-doc, my husband was a post-doc at the same institution, and when he would come to visit me in my lab, it was such a joy. That was when I was happiest, when everything that I loved was in one room. Now, our two daughters sometimes come to spend time with me in my office. That makes me very happy.

What do you consider to be your finest achievement?

I don’t think I’ve gotten there yet. I’ve been at UCLA six years, and I've had a lot of really amazing people come through my lab. I think my finest achievement will come when they go off and establish their own labs and do amazing things.

What are the qualities of a great scientist?

Perseverance is very important because a lot of times things fail, and you have to be willing to go back and try again or try doing things a little differently. Coupled with that is optimism, because you can’t keep coming back after failures if you’re not optimistic. And there’s skepticism, too. You have to be willing to take a hard look at your own data or at other people’s data, and to recognize what the limitations are and how that might influence our understanding of what it is the mice are trying to tell us.

What characteristic most defines you?

I think I do embody that optimism in the face of failure. Maybe that is because I think the process of doing science is really fun. Even if the result is negative or uninterpretable, I enjoy the challenge of going back and doing it better.

What is your greatest virtue?

I try to see people as whole people. I try to recognize their strengths as well as their weaknesses, and to leverage those strengths and work on shoring up their weaknesses. I try to do that with myself, as well.

What is your greatest fault?

I can take the excitement a little too far. I might get really wrapped up in some line of research or some experimentation, and then I’ll get ahead of myself with that and maybe not pay attention as I should to other projects going on in the lab.

What is your motto?

Something we ask ourselves a lot in the lab is, “What is the critical test?” So, that might, I guess, be considered a motto. Or maybe it is, “What are the mice trying to tell us?”

Whom do you most admire?

The women who have trained me. I believe that my ability to be a woman in science is very much helped by the women who came before me, who really had to deal with many more barriers than I’ve had to. Their trailblazing efforts have made it possible for me to not just conduct important research, but also to be able to bring my children with me to my workspace or to talks and to work in an environment that has become more accepting.

When do you not think about science?

It’s difficult for me to not think about science, but I know it is important to be able to detach a bit at times. It is most important for me to do that when I’m with my kids, and to just think about them and take joy in them. That is something that I've been working on getting better at.

What is your most treasured possession?

I try not to be very attached to possessions. I have nice things, but if I lost them, most would be replaceable. But if I ever lost my wedding rings — I think I would be crushed.

To which superhero do you most relate?

The Hulk. Bruce Banner is a scientist, he is an intellectual, but he has this other side of his personality that he tries to keep in control. I feel that other side, The Hulk, can be leveraged for strength. I think I have a little bit of that in the way that I try to mentor people, take them under my wing. I advocate for them. And if somebody crosses one of my people, I am not a happy camper.

What is the best moment of your day?

Seeing my kids after school. Those hugs are the best.

What is your definition of happiness?

Knowing what it is I need to do to move forward, being ready for something and able to adjust if needed.

What is your definition of misery?

Ruminating on previous errors.

What music do you listen to while you work?

I don’t listen to much music when I’m working because I like to focus. But when I need a pick-me-up, I listen to Latin music. I go back to the cumbias that I listened to as a child at family parties, and people would get up and start dancing. That really gives me a second wind.