UCLA scientists decode the ‘language’ of immune cells

UCLA life scientists have identified six "words" that specific immune cells use to call up immune-defense genes, an important step toward understanding the language the body uses to marshal responses to threats. In addition, they discovered that the incorrect use of two of these words can activate the wrong genes, resulting in the autoimmune disease known as Sjögren’s syndrome.

“Cells have evolved an immune-response code, or language,” says Alexander Hoffmann, PhD, Thomas M. Asher Professor of Microbiology and director of the Institute for Quantitative and Computational Biosciences at UCLA. “We have identified some words in that language, and we know these words are important because of what happens when they are misused. Now we need to understand the meaning of the words, and we are making rapid progress. It’s as exciting as the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, which enabled archaeologists to read Egyptian hieroglyphs.”

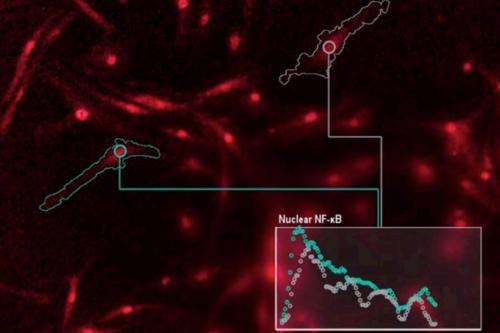

Immune cells in the body constantly assess their environment and coordinate their defense functions by using words — or signaling codons, in scientific parlance — to tell the cell’s nucleus which genes to turn on in response to invaders like pathogenic bacteria and viruses. Each signaling codon consists of several successive actions of a DNA-binding protein that, when combined, elicit the proper gene activation, in much the same way that successive electrical signals through a telephone wire combine to produce the words of a conversation.

For the study, the scientists analyzed how more than 12,000 cells communicate in response to 27 immune-threat conditions and generated a list of more than 900 potential words. Using an algorithm originally developed in the 1940s for the telecommunications industry, they monitored which of the potential words tended to show up when macrophages responded to a stimulus, such as a pathogen-derived substance. They discovered that six specific dynamical features, or words, were most frequently correlated with that response.

The team then used a machine-learning algorithm to model the immune response of macrophages. If they taught a computer the six words, they asked, would it be able to recognize the stimulus when computerized versions of cells were “talking?” They confirmed that it could. Drilling down further, they explored what would happen if the computer only had five words available. They found that the computer made more mistakes in recognizing the stimulus, leading the team to conclude that all six words are required for reliable cellular communication.

The researchers focused on words used by macrophages: specialized immune cells that rid the body of potentially harmful particles, bacteria and dead cells. Using advanced microscopy techniques, they “listened” to macrophages in healthy mice and identified six specific codons that correlated to immune threats. They then did the same with macrophages from mice that contained a mutation akin to Sjögren’s syndrome in humans to determine if this disease results from the defective use of these words.

“Indeed, we found defects in the use of two of these words,” Dr. Hoffmann says. “It’s as if instead of saying, ‘Respond to attacker down the street,’ the cells are incorrectly saying, ‘Respond to attacker in the house.’”

The findings, the researchers say, suggest that Sjögren’s doesn’t result from chronic inflammation, as long thought, but from a codon confusion that leads to inappropriate gene activation, causing the body to attack itself. The next step will be to find ways of correcting the confused word choices.

Many diseases are related to miscommunication in cells, but this study, the scientists say, is the first to recognize that immune cells employ a language, to identify words in that language and to demonstrate what can happen when word choice goes awry. Dr. Hoffman hopes the team’s discovery will serve as a guide to the discovery of words related to other diseases.