UCLA receives nearly $14 million from NIH to investigate gene therapy to combat HIV

Scientists at the UCLA Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research and colleagues have received a $13.65 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to investigate and further develop an immunotherapy known as CAR T, which uses genetically modified stem cells to target and destroy HIV.

The five-year grant, part of an NIH effort to develop gene-engineering technologies to cure HIV/AIDS, will fund a collaboration among UCLA; CSL-Behring, a biotechnology company in the United States and Australia; and the University of Washington–Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Scott Kitchen, an associate professor of medicine in the division of hematology and oncology, and Irvin Chen, director of the UCLA AIDS Institute at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, are leading the effort. The project will build on their previous research using CAR T therapy to combat the virus, which is constantly mutating and difficult to beat.

“The overarching goal of our proposed studies is to identify a new gene therapy strategy to safely and effectively modify a patient’s own stem cells to resist HIV infection and simultaneously enhance their ability to recognize and destroy infected cells in the body in hopes of curing HIV infection,” said Kitchen, who also directs the humanized mouse core laboratory for UCLA’s Center for AIDS Research and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center. “It is a huge boost to our efforts at UCLA and elsewhere to find a creative strategy to defeat HIV.”

The only known cure of an HIV-infected person was announced in 2008. The famous “Berlin patient” received a stem cell transplant from a donor whose cells naturally lacked a crucial receptor that HIV binds to in order to kill cells and destroy the immune system. The main problems with this approach, the researchers say, are that the donor and recipient have to be highly matched — often a rare event — and that it often fails to produce a sufficient amount of HIV-protected cells that can clear the virus from the body.

“Transplantation of blood-forming stem cells has been the only treatment strategy that has resulted in a functional cure for HIV infection,” Kitchen said. “Over 13 years after the first successfully cured HIV-infected patient, there is a substantial need to develop strategies that are capable of being used on everyone with HIV infection.”

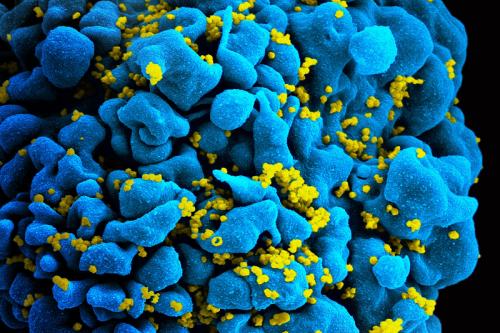

One of those strategies, CAR T, has been the subject of ongoing research at UCLA by Chen, Kitchen and others. This approach involves genetically engineering a patient’s own blood-forming stem cells to carry genes for chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs. Once these stem cells are modified and transplanted back into the patient, they form specialized infection-fighting white blood cells known as T cells — in this case, CAR T cells — that specifically seek out and kill HIV-infected cells. In a recent study, the UCLA scientists found that engineered CAR T cells not only destroyed infected cells but also lived for more than two years — the length of the study.

The thinking behind the NIH-funded project, the researchers say, is that a combination of CARs and broadly neutralizing antibodies may be a long-lasting, perhaps permanent, cure for HIV.

“Our work under the NIH grant will provide a great deal of insight into ways the immune response can be modified to better fight HIV infection,” said Chen, who is a professor of medicine and of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics at the Geffen School of Medicine. “The development of this unique strategy that allows the body to develop multiple ways to attack HIV could have an impact on other diseases as well, including the development of similar approaches targeting other types of chronic viral infections and cancers.”