Gene therapy delivers lasting immune protection in children with rare disorder

Key Takeaways

- A blood stem cell gene therapy co-developed by UCLA’s Dr. Donald Kohn restored immune function in 59 of 62 children with ADA-SCID, a rare and fatal immune disorder, with no serious complications reported.

- Without treatment, ADA-SCID is often fatal within the first two years of life, and current standard therapies — a stem cell transplant from a matched donor or lifelong enzyme injections — carry risks and high costs.

- The new study represents the largest and longest follow-up of a gene therapy of this kind, with 474 years of patient data including five children still healthy over a decade after receiving the treatment.

An experimental gene therapy developed by researchers at UCLA, University College London and Great Ormond Street Hospital has restored and maintained immune system function in 59 of 62 children born with ADA-SCID, a rare and deadly genetic immune disorder.

Severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency, or ADA-SCID, is caused by mutations in the ADA gene, which creates an enzyme essential for immune function. For children with the condition, day-to-day activities like going to school or playing with friends can lead to dangerous, life-threatening infections. If untreated, ADA-SCID can be fatal within the first two years of life.

The current standard treatments — bone marrow transplant from a matched donor or weekly enzyme injections — come with limitations and potential long-term risks.

The experimental gene therapy offers a new approach. Doctors collect a child’s blood stem cells, which create all types of blood and immune cells, and use a modified lentivirus to deliver a healthy copy of the ADA gene. Once infused back into the patient, the corrected stem cells begin producing healthy immune cells capable of fighting infections. Development of immune cells starts shortly after the gene-modified stem cells are reinfused, but it takes six to 12 months for the immune system to reconstitute to normal levels.

In a study published today in the New England Journal of Medicine, senior author Dr. Donald Kohn of UCLA and co-first authors Dr. Katelyn Masiuk, a former clinical project lead in the Kohn lab, and Dr. Claire Booth of GOSH report long-term outcomes for children treated with the gene therapy between 2012 and 2019.

“These results are what we hoped for when we first began developing this approach,” said Kohn, a distinguished professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. “The durability of immune function, the consistency over time and the continued safety profile are all incredibly encouraging.”

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, Orchard Therapeutics and the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Research Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre.

Lasting immune function and a strong safety profile

The study represents the largest and longest follow-up of a gene therapy of this kind to date, with 474 total patient-years of follow-up data — including five patients who received the therapy more than a decade ago.

For the 59 patients successfully treated, immune function has remained stable beyond the initial recovery period, with no treatment-limiting complications reported.

“What’s most remarkable is that everything has been completely stable beyond the initial three-to-six-month recovery period,” said Kohn, a distinguished professor of pediatrics who has been working to develop gene therapies for ADA-SCID and other blood diseases for 40 years. Most adverse events were mild or moderate and related to routine preparatory procedures rather than the gene therapy itself.

“Treatment was successful in all but three of the 62 cases, and all of those children were able to return to current standard-of-care therapies,” Kohn said. Two of these patients went on to receive bone marrow transplants and one was receiving ADA enzyme injections while preparing for a transplant at the time of the data cutoff.

Advancing accessibility through improved methods

More than half of the children treated received a frozen preparation of corrected stem cells. These children experienced similar outcomes to those who received stem cells that were not frozen. The success of the cryopreservation method has important implications for making the therapy more accessible to patients worldwide.

“The freezing approach allows children with ADA-SCID to have their stem cells collected locally, then processed at a manufacturing facility elsewhere and shipped back to a hospital near them,” said Masiuk, who now works for Rarity PBC, a public benefit corporation founded by Kohn lab alumni. “This removes the need for patients and their families to travel long distances to specialist centers.”

The frozen cell approach also allows for more comprehensive testing and quality control before treatment, as well as more precise dosing of the conditioning chemotherapy used to prepare patients for the gene therapy.

The path toward FDA approval

With support from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the UCLA team is now working to complete the steps necessary to apply for FDA approval. Rarity PBC has licensed the gene therapy from the UCLA Technology Development Group and is partnering with commercial manufacturing organizations to produce the therapy under pharmaceutical-grade conditions.

“Our goal is to have this therapy FDA-approved within two to three years,” Kohn said. “The clinical data strongly supports approval — now we need to demonstrate that we can manufacture the treatment under commercial pharmaceutical standards.”

Inside the life gene therapy made possible: Eliana’s story, 10 years later

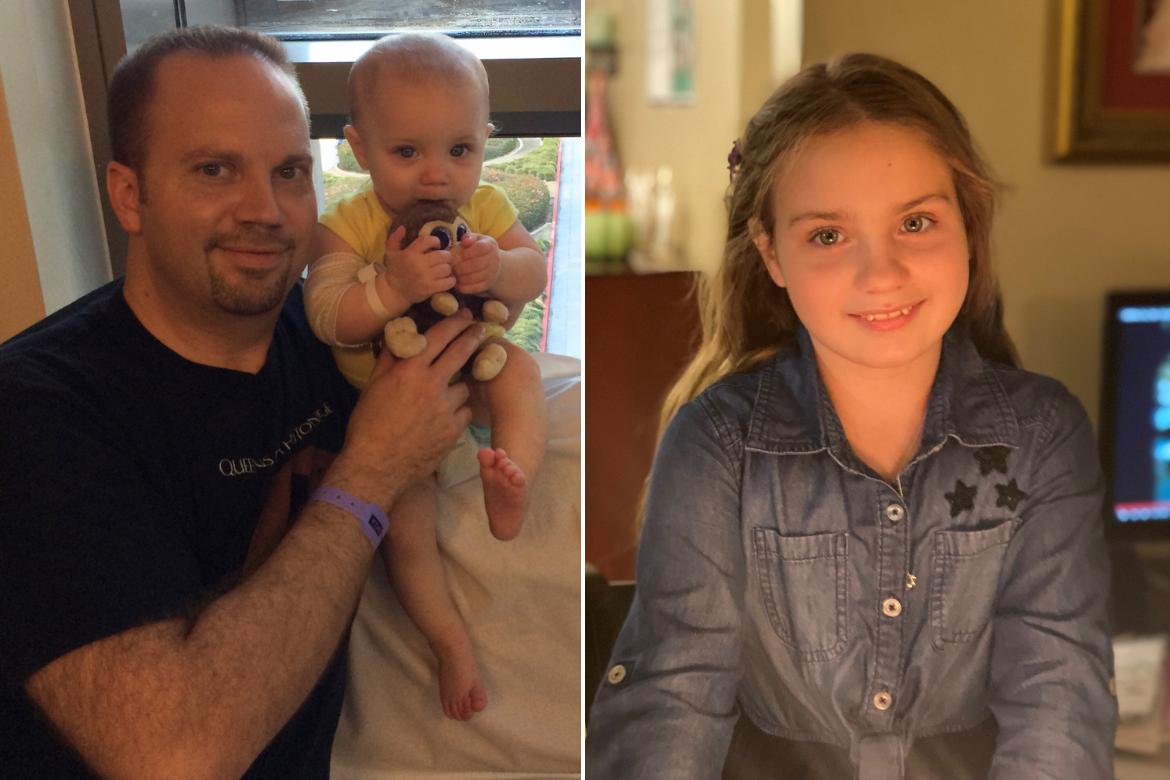

Eleven-year-old Eliana Nachem of Fredericksburg, Virginia, is starting sixth grade with dreams of becoming an artist. It’s a remarkably ordinary life that once seemed impossible.

After Eliana was diagnosed with ADA-SCID at 3 months old in 2014, she lived in complete medical isolation. No pets, no contact with the outside world, with HEPA air filters running constantly and all food and toys sterilized.

“We had to get rid of our dog and cat, she couldn’t go outside, and I had to stop breastfeeding,” her mother, Caroline, recalled. “Formula had to be consumed within an hour or thrown out. Everything that might harbor germs was dangerous to her.”

Facing the choice between gene therapy and bone marrow transplantation, Caroline and her husband, Jeff, carefully researched both options. A phone call from Dr. Kohn about compelling new results from another patient proved decisive.

“The data was absolutely stunning — like a bouquet of flowers over the phone,” Caroline said. “Almost overnight, we knew we had to do this.”

In September 2014, at 10 months old, Eliana received her corrected cells at UCLA. Caroline and Jeff described watching the infusion as their daughter’s “rebirth” — her own genetically modified cells carrying the promise of a normal life.

“I remember thinking, she’s born again, and now we just get to watch her grow,” she said.

A decade later, that promise has been fulfilled. Despite some early complications during her immune system’s recovery, Eliana has thrived, attending public school, playing basketball and living the unrestricted childhood her parents once could only dream of.

“Now the biggest thing I have to worry about is her entering middle school and bossing me around,” Caroline said with a laugh. “I am eternally grateful to every single scientist, doctor, lab worker, nurse, hospital security guard — all the people who had anything to do with this gene therapy coming into existence and saving her.”