3 ways UC science is healing broken hearts

More than 800,000 Americans will have a heart attack this year. Fortunately, most will survive the traumatic event — but many will emerge with hearts damaged beyond repair.

“Many tissues in your body, such as the skin or the liver, can multiply and grow back. But the heart muscle is unable to do that,” says UCLA cardiologist and professor Arjun Deb. “When your heart muscle dies, you lose that muscle forever.”

But thanks to UC research backed by federal funding, this reality is quickly changing. Today scientists across UC are developing new treatments that don’t just prevent heart damage from getting worse, but — for the first time in medical history — actually help the heart heal.

Learn how three UC labs are tackling the biggest cardiovascular challenges and coming up with solutions that could soon help save thousands of lives every year.

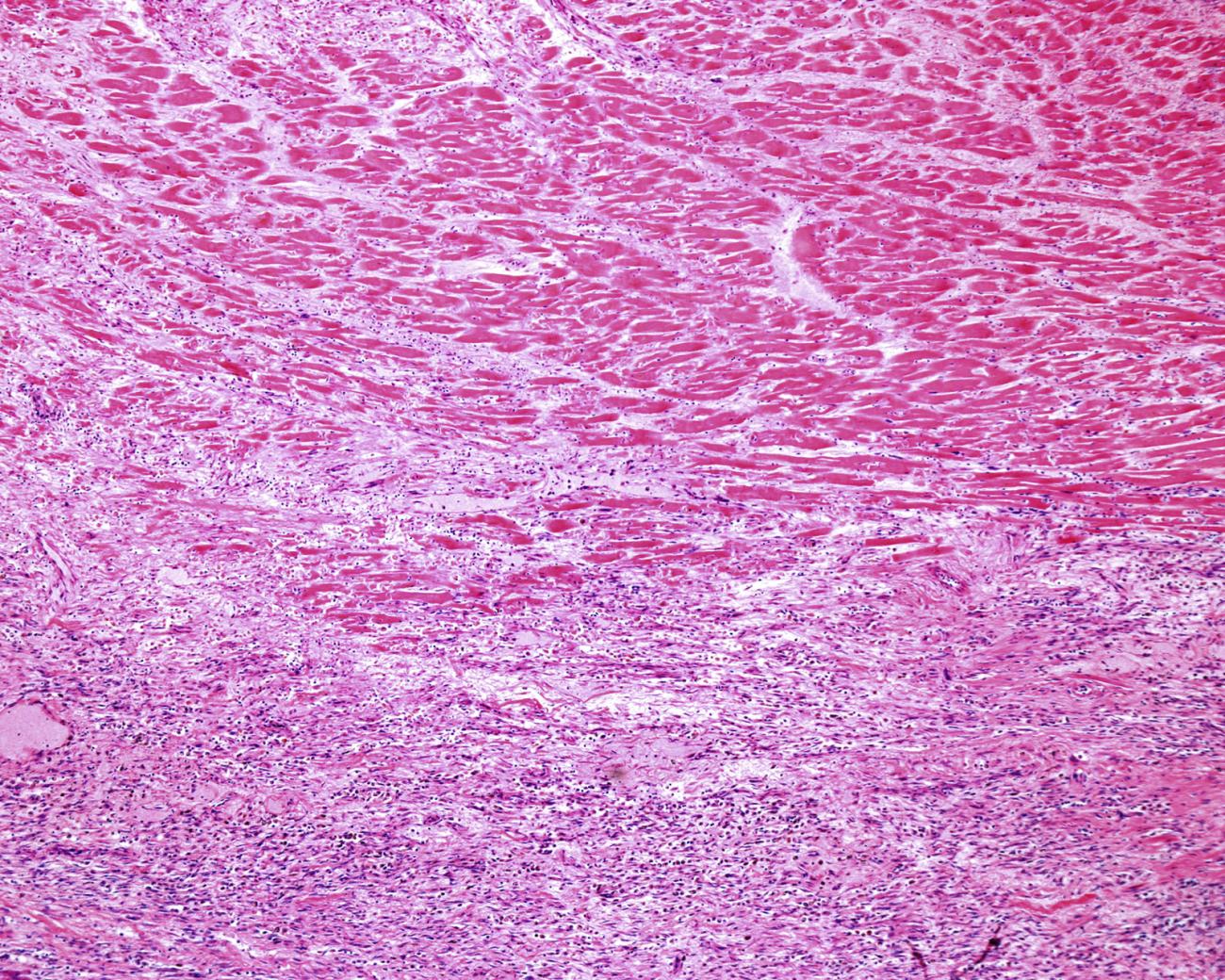

Problem #1: The heart survives by scarring — but that fix creates long-term failure.

After a heart attack, your body hastens to form a scar over dead tissue. That scar saves your life in the short run, bolstering the heart wall to avoid a fatal rupture. But scar tissue is stiffer than the muscle it replaces, so it can’t contract, and it also can’t conduct the electrical signals that keep the heart pumping.

The surviving muscle works harder to compensate, kicking off a spiral of stress on the whole organ. Eventually, many survivors develop heart failure, the point at which one’s heart no longer work well enough to circulate the blood the rest of our organs need. And once you have heart failure, you have about a one in two chance of dying within five years — a prognosis that’s comparable to the worst forms of cancer.

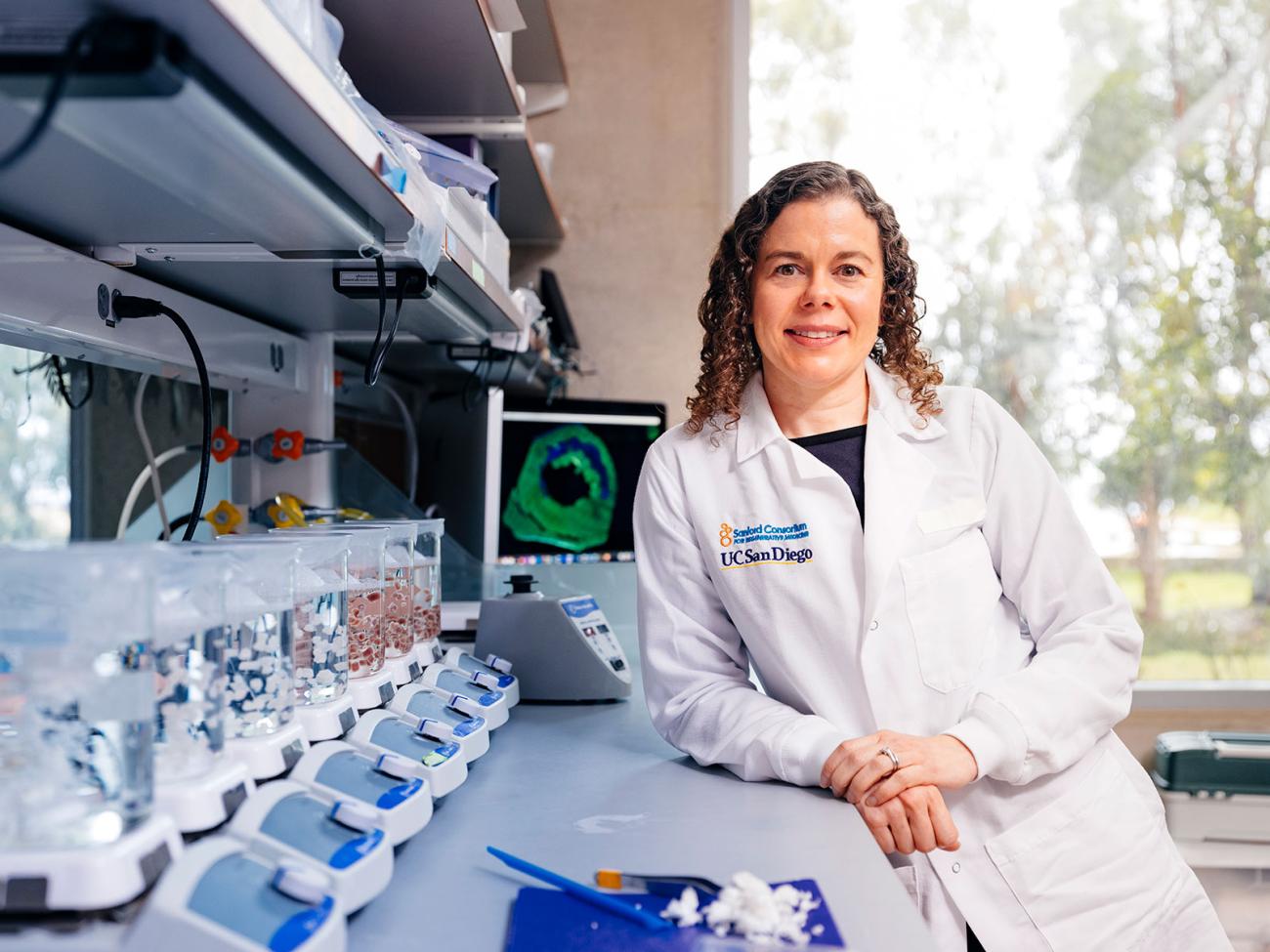

Solution #1: An injectable gel reduces scarring and preserves living muscle.

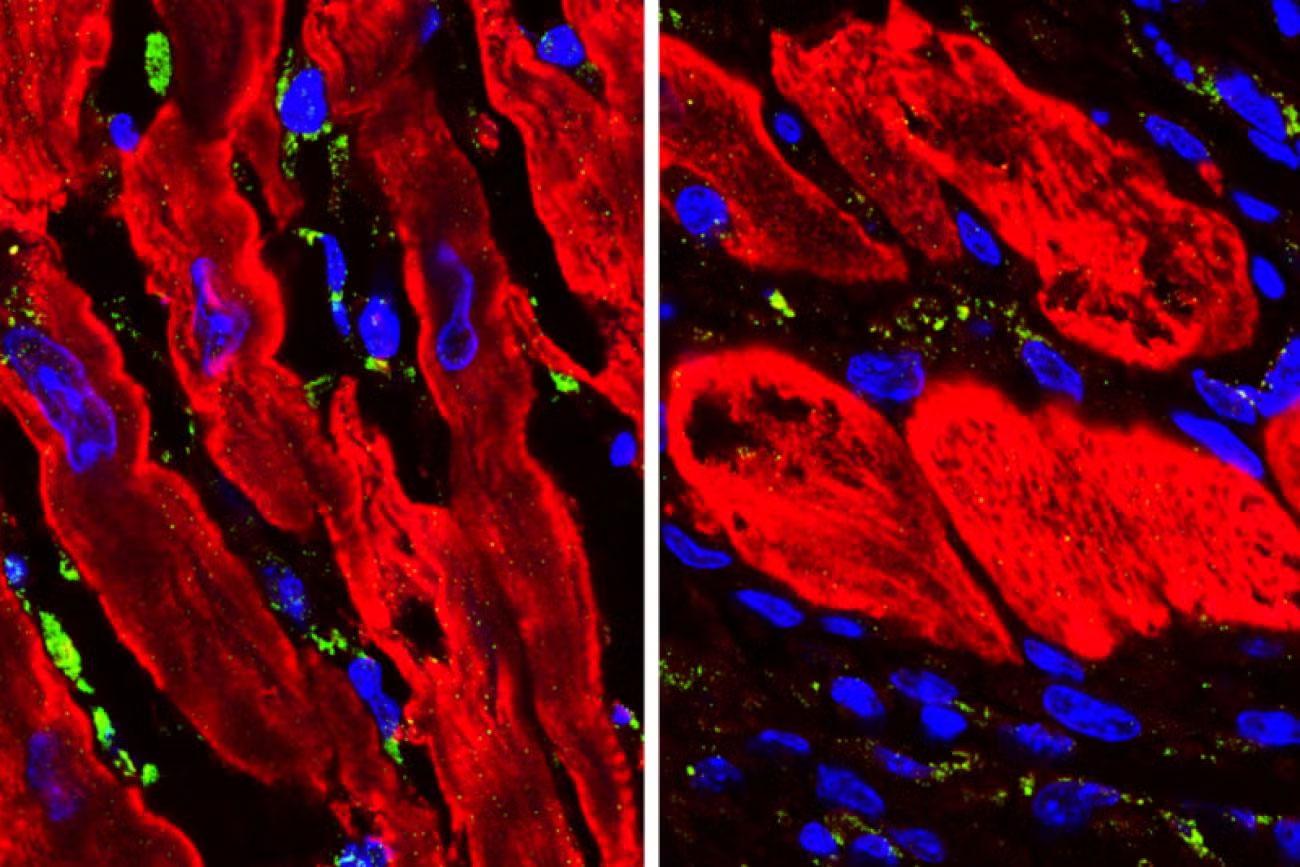

UC San Diego bioengineering professor Karen Christman has done groundbreaking work treating injured hearts with extracellular matrix, or ECM, a substance our bodies produce to give our tissues shape and form. She’s developed a gel made of ECM that can be administered in the aftermath of a heart attack. Once on scene, ECM both calms inflammation in damaged tissues and organizes itself into a structure that recruits new cells like those that form blood vessels. “That stimulates the heart to have less scar tissue and preserve more cardiac muscle,” Christman says.

Christman demonstrated that it’s safe to inject ECM directly into the heart with a catheter in a 2019 clinical trial. Patients who got the gel were eventually able to walk faster than those that didn’t, an indication that their hearts were working better. Now, she’s planning for a new clinical trial testing whether ECM can be delivered via a blood vessel that feeds the heart, which would enable doctors to administer it sooner and less invasively.

Problem #2: The heart can’t afford to take time off to heal.

If you break a bone or slice your finger, you can rest and protect that part of your body while new cells grow and organize. Not so your heart: if it stops working, you’ll die within minutes. As a result, our hearts have evolved to prioritize stability and survival over repair. This evolutionary trade-off plays out following a heart attack, where energy levels in contracting heart muscle drop within minutes, and a lot of the heart muscle dies and is replaced by scar tissue.

UCLA cardiologist Arjun Deb discovered that this change in energy levels is caused by high levels of a protein called ENPP1. This protein can help lower damaging inflammation in healthy tissues, but high ENPP1 after a heart attack starves injured cells of the energy they need to heal and get back to work. Instead, those cells stay stressed out for longer and are likelier to ultimately die, feeding the process that eventually leads to heart failure.

Solution #2: A new drug re-energizes damaged heart cells by lifting a molecular brake.

Once he discovered ENPP1’s function in the heart, Deb developed a molecule that blocks it from working in the short run. With ENPP1 suppressed, heart cells get more energy and fuel they need to heal. When Deb gave this molecule to animals shortly after a simulated heart attack, just 5 percent of them developed heart failure, compared with over 50 percent of mice who didn’t receive treatment. Following FDA clearance, Deb is now leading a phase 1 clinical trial to test the safety of the molecule in humans.

“This research represents a radical departure from existing lines of investigation which have led to the current drugs,” says Deb. Most of these meds have been used for decades, and while they can slow the rate of tissue decline after heart attack, they can’t reverse damage that’s already done. Deb believes he’s on to a drug that can.

This research has been funded entirely by state and federal agencies, including the National Institutes of Health. “My team and I are enormously grateful to the NIH for believing in us and we hope to deliver soon to the American people a new therapy for heart disease,” he said.

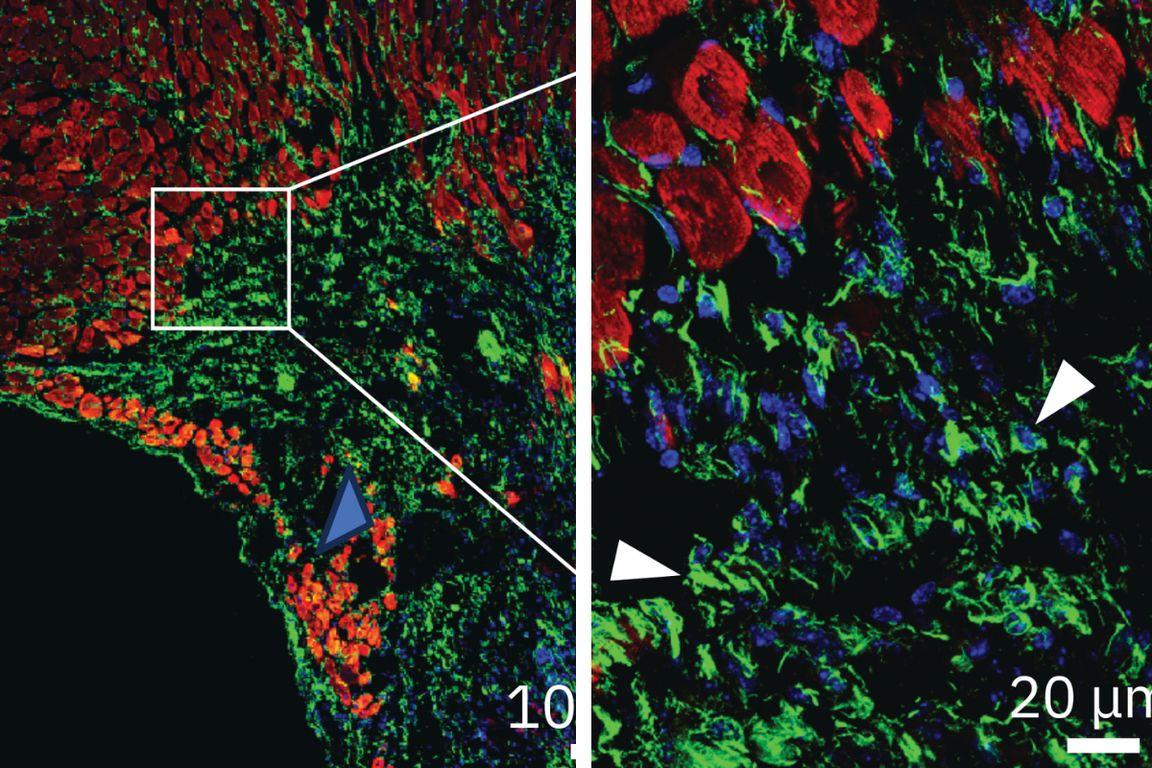

Problem #3: Humans lost the ability to regrow heart muscle — but some animals never did.

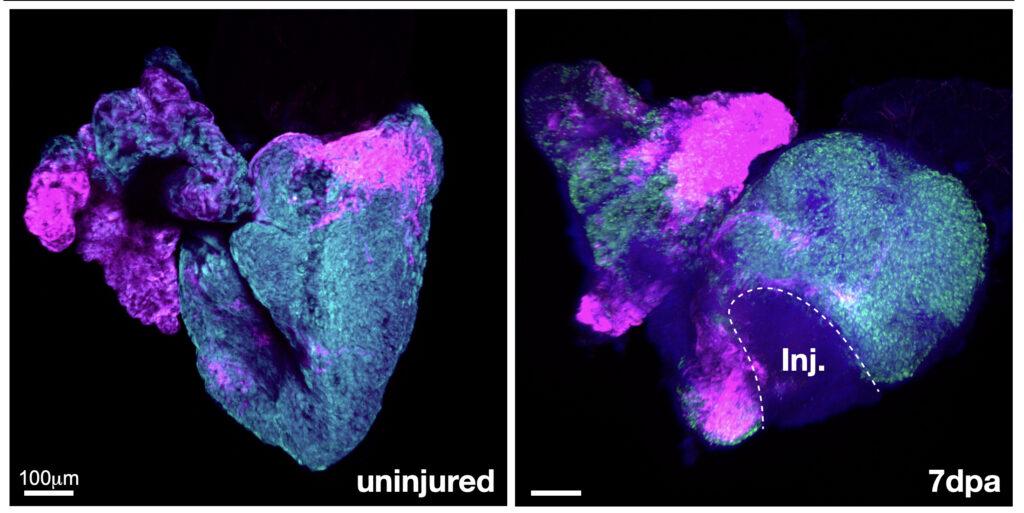

Unlike humans, many animals actually can regrow heart muscle. UC San Francisco research suggests early mammals lost this ability as a trade-off for warm-bloodedness over 200 million years ago, but the zebrafish has kept it to great effect: When UC Berkeley researchers snipped out big chunks of zebrafish hearts, their wounds healed completely within a month.

With support from NIH, UC Berkeley professor Megan Martik ran this experiment to better understand how zebrafish do it. Martik used genomics to identify the handful of genes that kicked into gear as the animals regrew their hearts. She found that the genes responsible for regenerating heart muscle after injury are the same as the genes expressed when the animals’ hearts were first forming during embryonic development, as cells mature into cardiac muscle and other tissue.

Solution #3: By mimicking zebrafish genetics, scientists induce heart re-growth in humans.

Martik discovered that humans carry many of the same genes as zebrafish, and these genes express themselves in similar ways while our hearts are first developing. But our versions of these genes don’t reactivate later in life in response to injury, unlike those of the zebrafish. Now, Martik is using CRISPR to tweak gene expressions in stem cell models of the human heart so they more closely mimic those of the zebrafish, with a goal of inducing our heart cells to regenerate.

Thanks to steady federal funding from the National Institutes of Health, Martik estimates therapies that induce human heart tissue to regenerate after a heart attack or other injury may be just a few years away.

Speak up for life-saving medical research

Each of these promising discoveries has advanced with federal funding from the National Institutes of Health, or NIH. In the most recent budget negotiation, the federal government proposed deep cuts to federally funded science agencies like NIH, which would have slowed down discovery and taken a toll on our economy, jobs and families.

Through UC’s Speak Up for Science campaign, we asked our community to contact their representatives and urge them to reject these cuts. Congress got the message: Last week, lawmakers passed a federal budget that preserves bipartisan funding for NIH and other science funding agencies for the year to come. It’s a huge win at a tumultuous time for American science, but our work isn’t done.

As we look to the next federal fiscal year, we’re counting on our community to once again help make sure we protect federal research funding to boost discovery and grow the economy and America’s global leadership in research. Join the UC Advocacy Network to get the latest updates from UC and follow our Speak Up for Science campaign to stay informed.