UCLA research helped pave the way to these 8 major cancer-fighting drugs

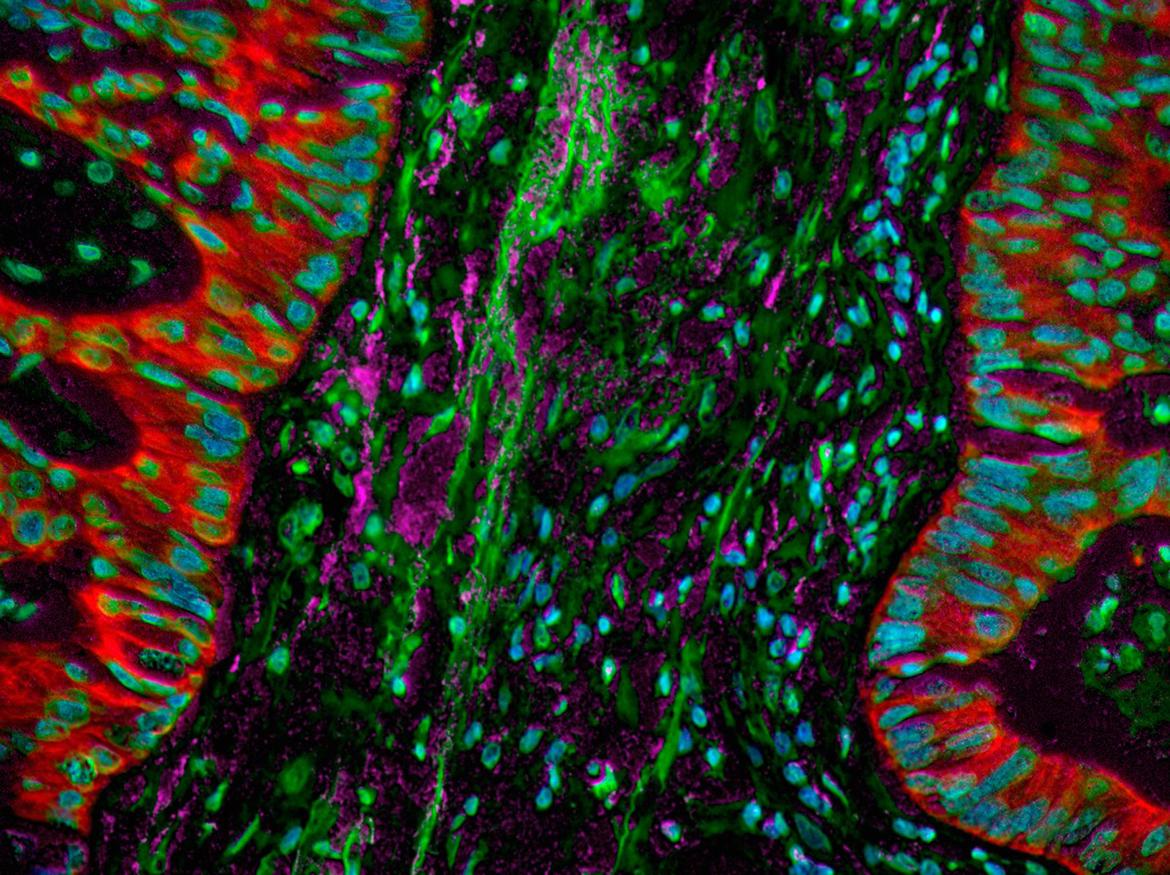

Though major advancements have been made to treat cancer, it remains one of the leading causes of death — not just in the U.S., but in the world. UCLA researchers have long been committed to being at the forefront of the fight against this deadly disease. Driven by a desire to help and find answers to complex medical problems, UCLA’s cancer research has been deeply impactful, with millions of people receiving drugs and therapies developed in Bruin labs.

And that mission to improve and save lives continues, thanks to the ongoing research by scientists and doctors across campus, connected through the UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, who are constantly looking for new ways to treat cancer.

Here are just some of the cancer-fighting drugs that were developed by or stemmed from research at UCLA:

Herceptin (trastuzumab)

In the early 1990s, women who were diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer weren’t expected to live more than three to five years after diagnosis. That changed when a team of scientists led by Dr. Dennis Slamon, chief of hematology/oncology at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, developed what became known as Herceptin. “(W)e wanted to try and study the cancer cell at a molecular level … identify what was broken and find out if we could target that specifically,” Slamon previously told UCLA Health. “The hope would be if we could target that specifically, we’d come up with something that was hopefully more effective and safer because normal cells wouldn’t have what was broken, only the cancer cells.” Since its introduction on the market in 1998 to treat HER2-positive breast cancer, Herceptin has benefited millions of women worldwide.

Xtandi (enzalutamide) and Erleada (apalutamide)

After skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in the United States, with 1 in 8 developing prostate cancer in their lifetime, according to the American Cancer Society. But since 2012, hundreds of thousands of patients with advanced-stage prostate cancer have benefited from Xtandi, developed by UCLA distinguished professor of chemistry Michael Jung and Dr. Charles Sawyers, then of the UCLA Department of Medicine. In 2018, their second drug, prescribed under the brand name Erleada, had its clinical trial stopped two years ahead of time after early success and received FDA approval that same year. “The phase 3 clinical trial found that Erleada gives men an extra two years of healthy life before their cancer spreads,” Jung previously said. “To give someone an extra two years of healthy life is fabulous.”

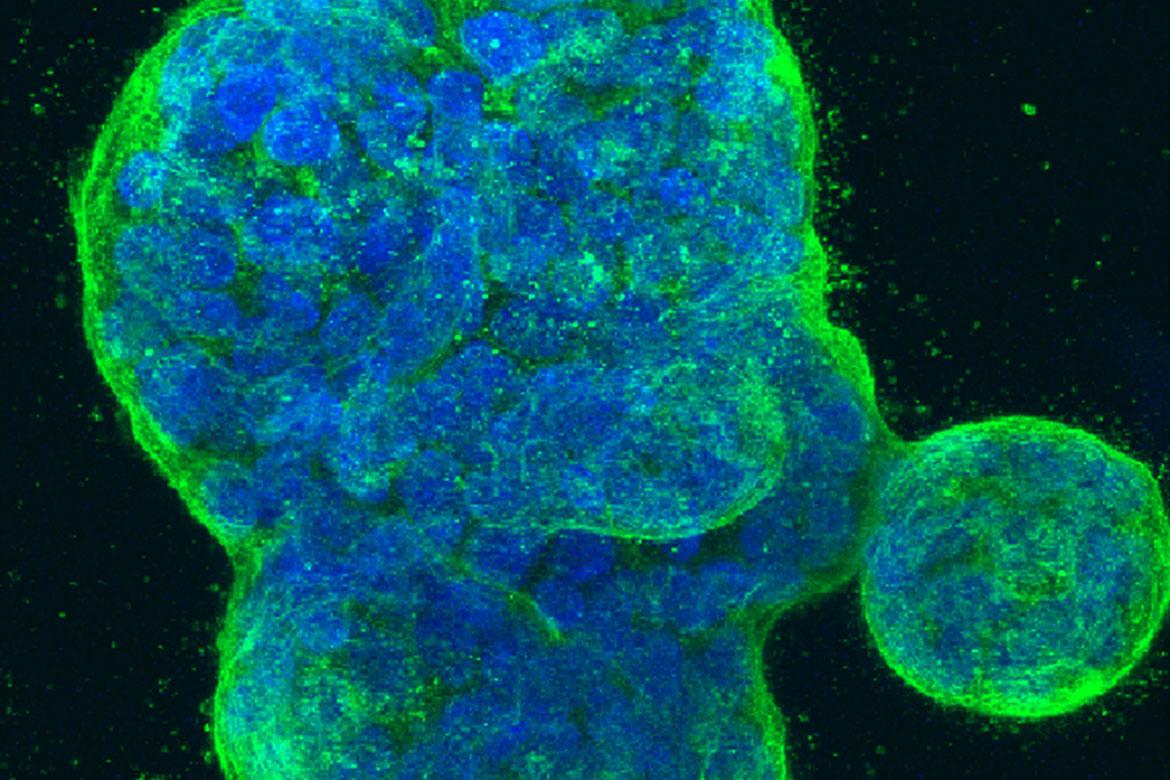

Ibrance (palbociclib)

In the mid-2000s, when a team of UCLA Health Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center researchers led by Slamon and Dr. Richard Finn began investigating a compound developed by Pfizer called PD-0332991, few people believed it would amount to much. Today, that drug, marketed under the name Ibrance (palbociclib), has transformed the treatment of estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) and HER2-negative breast cancer, helping hundreds of thousands of patients worldwide. Their work not only led to the approval of palbociclib to be used in combination with hormonal therapy — it also opened the door to an entirely new class of therapies known as CDK4/6 inhibitors. These drugs, which slow cancer cell division, have since become the standard of care for advanced ER+/HER2- breast cancer and are now showing promise in early-stage disease.

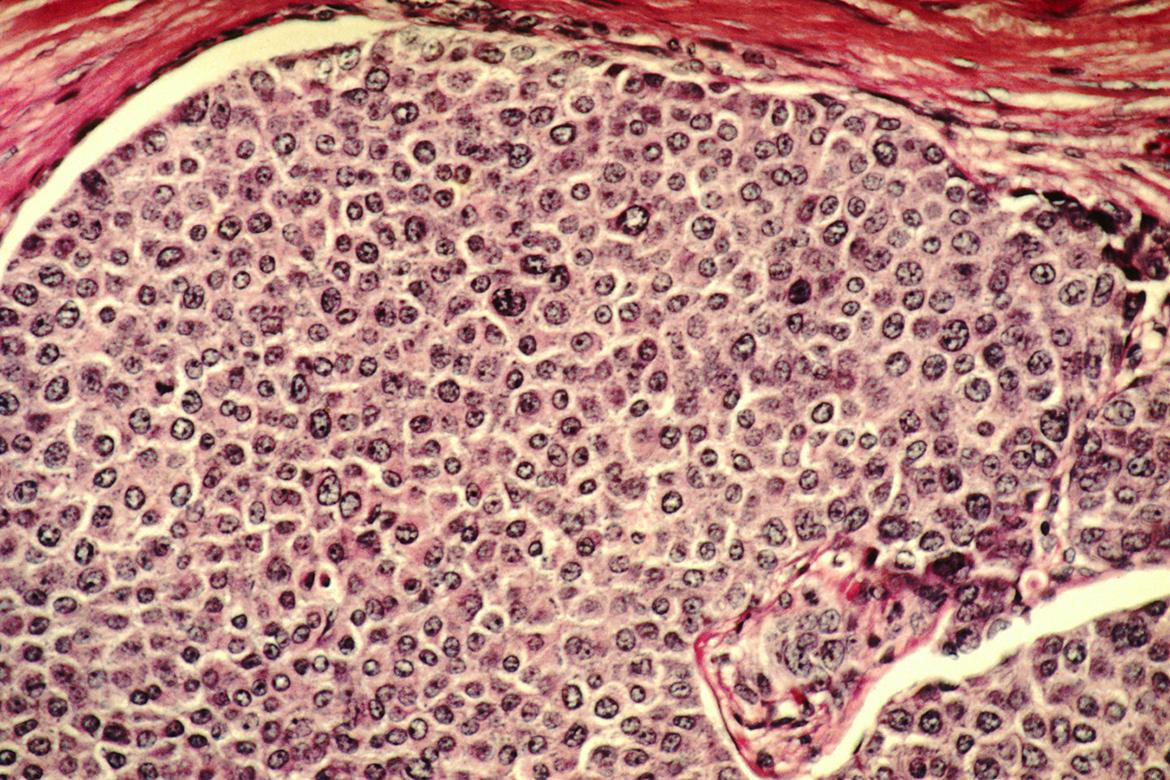

Gleevec (imatinib)

In the mid-1980s, UCLA professor Dr. Owen Witte discovered that the abundance of a class of enzymes called tyrosine kinase caused chronic myelogenous leukemia symptoms. Witte’s work led to research led by Brian Druker at Oregon Health & Science University into molecules that could inhibit tyrosine kinase. And in the 1990s, pharmaceutical company Novartis began work on manufacturing Gleevec, the first targeted therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia, marking a transformative shift from traditional chemotherapy to precision medicine. Gleevec was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2001.

Kisqali (ribociclib)

In the early 2000s, a team of researchers led by Slamon led the discovery program that found that cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors are effective in treating HR-positive breast cancer. Their work ultimately helped pave the way to FDA approval of ribociclib and other related drugs to treat advanced, metastatic breast cancer.

Slamon also led the NATALEE clinical trial of a new drug regimen using ribociclib to help reduce recurrence in early-stage breast cancer. In March 2024, the results showed that the addition of ribociclib with endocrine therapy significantly extended the time a person with Stage 2 or 3 HR-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer lives without the cancer returning. Results in the study led to FDA approval in September 2024.

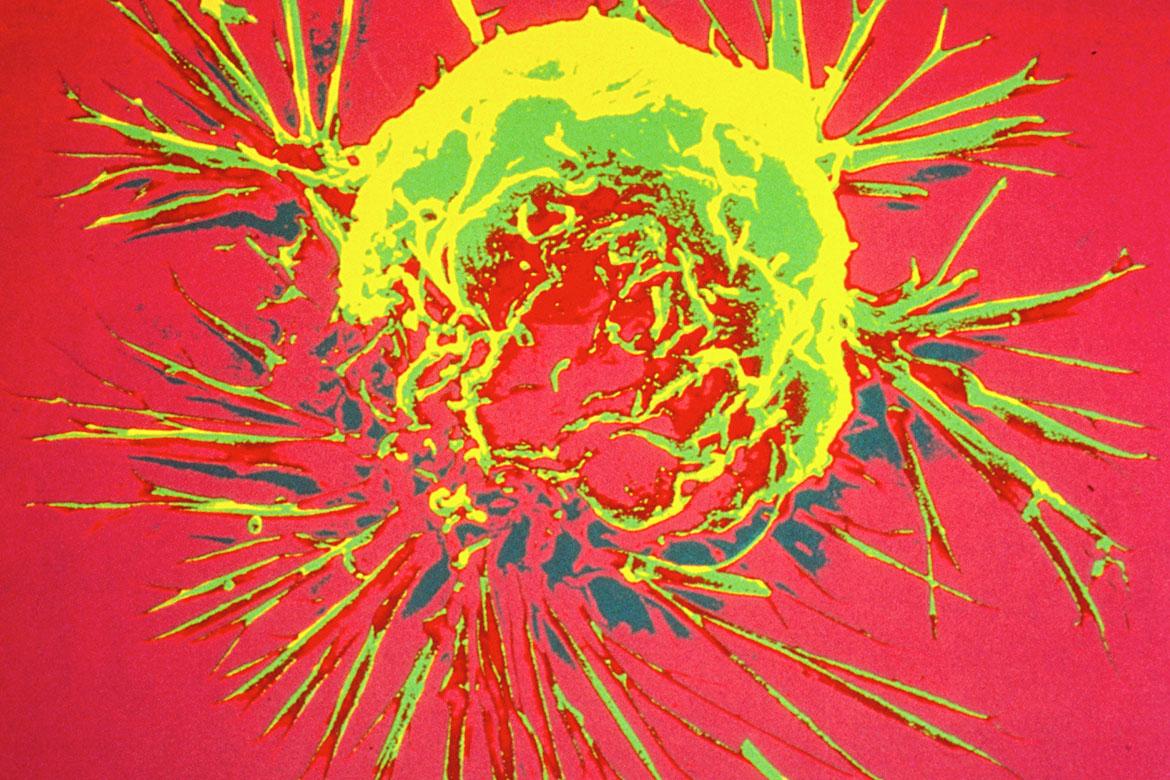

Keytruda (pembrolizumab)

When pembrolizumab was first developed, it had limited use. UCLA professor Dr. Antoni Ribas was part of changing that when he helped develop and demonstrate the effectiveness of the drug to treat advanced melanoma. The largest phase 1 study in the history of oncology, Keytruda was tested on more than 600 patients with melanoma that had spread throughout their bodies. The research was conducted at UCLA and 11 other sites in the U.S., Europe and Australia, with Ribas as the study’s principal investigator. Based on the results, the FDA granted pembrolizumab accelerated approval in 2014.

Building upon the immunologic principles from Ribas’ research, UCLA’s Dr. Edward Garon led the largest study published to date using Keytruda to treat lung cancer. This work helped pave the way to the drug’s approval for use in advanced non-small cell lung cancer in 2015.

Cyramza (ramucirumab)

Cyramza first received FDA approval to treat lung cancer in 2014, following a phase 3 clinical trial at UCLA and other centers in 26 countries on six continents. It was the first drug in a decade to demonstrate a survival benefit in people with a specific type of lung cancer who had already received treatments. “It is exciting to see that by adding ramucirumab (Cyramza) to docetaxel, patients were able to live longer than those who were treated with the standard approach,” Garon, the study’s principal investigator, said at the time. “We are pleased to have access to a drug that lengthens survival time in a population of lung cancer patients who often have few treatment options.” Cyramza has gone on to be used for the treatment of a variety of cancer types.